Babies can learn multiple languages from birth—and they’ll slow the onset of dementia if they do

Here’s what happened this week in language and linguistics.

There was all sorts of interesting research in linguistics this week! Let’s dive in!

Welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Dispatch, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics.

📢 Updates

Announcements and what’s new with me and Linguistic Discovery.

The International Conference on Language Documentation & Conservation (ICLDC) was held last week in Honolulu, and while I didn’t get a chance to attend myself, ICLDC is one of my favorite conferences I’ve attended. Documentary linguists come together to present on how they’re working to document and revitalize languages all over the world. The conference is held every other year at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. You can see the 2025 program here, and even watch talks from the 2023 conference here.

Relatedly, U Hawaii also publishes the open access journal Language Documentation & Conservation, filled with great articles on best practices in documentary linguistics. I highly recommend looking at their article archive if you’re interested in getting into language documentation.

You’ll notice I’ve added an Errata section to the end of the newsletter this week. It is both a blessing and a curse of writing online to large audiences that everything you write is subjected to detailed scrutiny, which means I often quickly learn either where I went wrong, where I could have added more detail, or where I should clarify. Plus, one of the trickiest things about doing science communication online is determining the right level of detail at which to present ideas, and it’s easy to miss the target. So I suspect I’ll be making ample use of the Errata section going forward.

I also have a short policy statement about errata here for anybody interested.

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week’s content from Linguistic Discovery.

Last week Trump made English the official language of the U.S.—sort of. Here’s what the order does, and what the demographics of language looks like in the U.S. today:

📰 In the News

Language and linguistics in the news.

Here’s a neat article about how forensic linguistics enabled Scotland police to track down the Edinburgh nail bomber:

How Police Scotland used linguistic specialist to track down Edinburgh nail bomber (Scottish Daily Express)

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

Babies can naturally learn multiple languages from birth

[M]ost babies in Accra, [Ghana’s] capital, grow up in environments where they are exposed to between two and six languages from birth.

Yes, you read that correctly. Multilingual babies! I think it’s important to realize, however, that this degree of multilingualism has been incredibly common for most of humanity’s history. Two facts help to understand this:

First, most languages throughout history have been tiny, with just a few thousand speakers. It wasn’t until the Agrarian Revolution and the rise of urban developments that languages began to grow bigger. (Below are two awesome books that cover this topic if you’re interested in learning more.)

Second, prehistoric peoples were much more mobile than most people today tend to assume, and engaged in long-distance trade networks.

Taken together, these facts mean that prehistoric peoples were frequently interacting with other languages. You only had to travel to the territory of the second-to-next tribal group over, and their language probably wasn’t mutually intelligible with yours.

A new study explores just how this multilingualism happens in Ghanian infants. The researchers discovered that infants were exposed to multiple languages from birth through both direct sources (caregivers, family members) and indirect sources (media), and that the large extended family structures in Ghana abetted this multilingualism. Here’s the reporting and the original research study:

Babies can naturally learn multiple languages from birth (Earth.com)

Omane, Benders, & Boll-Avetisyan. 2025. Exploring the nature of multilingual input to infants in multiple caregiver families in an African city: The case of Accra (Ghana). Cognitive Development 74. DOI: 10.1016/j.cogdev.2025.101558

How to learn a language like a baby

If you want to be like those multilingual babies I mentioned earlier, The Conversation has a great article on “How to learn language like a baby”. You might be surprised to learn that reading in the new language you’re learning can actually slow down your learning! Spelling seems to interfere with our ability to learn pronunciations and prosody. So for your next language, you might consider taking the illiterate approach!

How to learn a language like a baby (The Conversation)

Chládková et al. 2025. Tuning in to the prosody of a novel language is easier without orthography. Bilingualism: Language & Cognition. DOI: 10.1017/S1366728925000082

Why being bilingual really does seem to delay dementia

Those multilingual babies also have the benefit of being less likely to develop dementia early in life. More and more research shows that bilingualism has incredible cognitive benefits, among them being that it delays the onset of dementia. And it’s never too late! “learning another language in adulthood [still] provides benefits to brain health”, says Viorica Marian, author of the recent book The power of language: How the codes we use to think, speak, and live transform our minds (Amazon | Bookshop). New Scientist reports here:

Why being bilingual really does seem to delay dementia (New Scientist)

How the brain decodes changes in pitch

A study in Nature Communications last week showed that a specific part of the brain known as Heschl’s gyrus (HG) is involved in recognizing pitch accents.

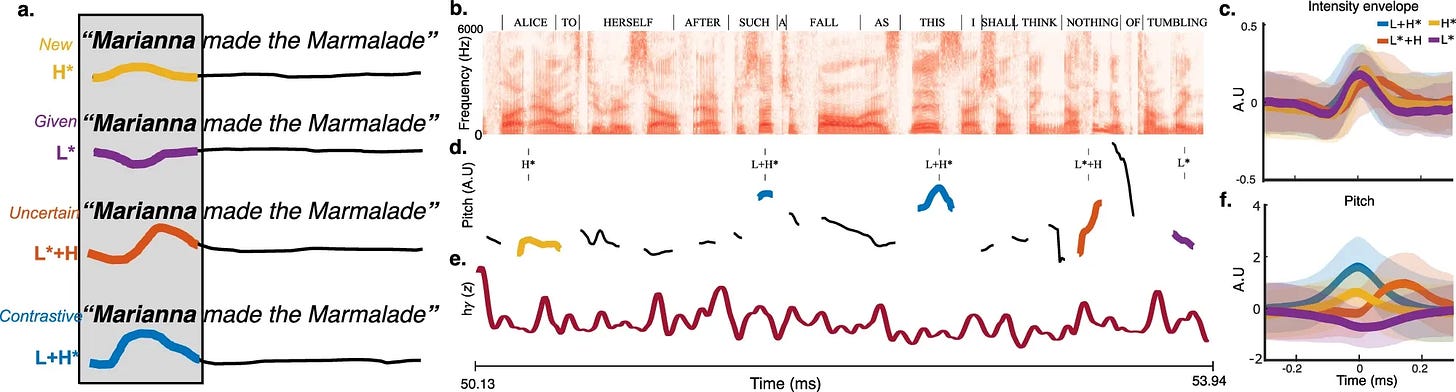

Now, the term pitch accent gets a lot of different uses in linguistics, and there’s debate among typologists as to whether pitch accent is even a coherent concept. But what the researchers here are referring to is how English speakers stress certain words in an utterance. Not only can speakers stress different words, but they can stress the same word in different ways. If you stress a word with a falling pitch it means something very different than if you stress it with a rising pitch. These different stress patterns are called pitch accents. You can see in section (a) on the left in this example how the same word, Marianna, is given four different pitch accents.

☝️ Pitch in language is the same thing as musical pitch, so you can think of the pitch contours in section (a) of the diagram above as almost like musical notes—a higher line indicates a higher pitch. You could leave out the words and literally whistle each of these pitch contours.

Pitch accent itself is a subtype of prosody—how we use pitch and rhythm and other phonetic cues to signal different units of discourse. Prior to this study, it was thought that most processing of prosody in the brain occurred in a region called the superior temporal gyrus (STG). This study shows that not only does this prosodic processing happen in Heschel’s gyrus (HG) as well, but that HG does most of the work in understand pitch accents.

Moreover, HG seems to create abstract representations of different pitch accents. If you think about what we’re doing when we listen for pitch accents, it’s an incredible feat. Each person has a different pitch range, for starters, so that one person’s high pitch can be, in absolute terms (Hertz), another person’s low pitch. Pitch is also relative, meaning that a high pitch accent on a low-pitch phrase may in fact be lower, in absolute terms, than a low pitch on a high-pitch phrase. The fact that humans are capable of detecting similar pitch accents across different speakers and contexts is pretty remarkable, and it means that we have to create very abstract representations of these pitch contours in our minds, independent of the particular contexts we hear them in. This study shows that this is exactly what happens in the human brain, and furthermore that other primates like macaque monkeys do not create these kinds of abstractions. While humans show different types of brain activity for the different pitch accents, the macaque monkey did not.

A final remarkable feature of this study is that the participants each had electrodes implanted deep in their cerebral cortex. Usually, neurolinguistic studies are noninvasive and rely on readings taken at the surface of the skin. However, these participants already had electrodes implanted in their brains because they were receiving treatment for severe epilepsy, allowing for this pioneering experiment.

Here’s some reporting on the study:

It's not just what you say—it's also how you say it: How the brain decodes changes in the pitch of speech (Medical Xpress)

Speech processing in the brain goes beyond words (Earth.com)

And here’s the original research article:

Gnanateja et al. 2025. Cortical processing of discrete prosodic patterns in continuous speech. Nature Communications 16: 1947. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-56779-w

📃 This Week’s Reads

Interesting articles I've come across this week.

Interjections like English huh, um, and mm-hmm play a crucial role in languages, helping speakers control the flow of speech, manage turn-taking, show they’re being pensive, and indicate their attitude towards information.

“A key part of grounding is working out what each participant thinks about the other’s knowledge.”

Popular Science interviews Mark Dingemanse about his recent research on interjections:

Huh? The valuable role of interjections (Popular Science)

You can read the original review article here:

Dingemanse, Mark. 2024. Interjections at the heart of language. Annual Review of Linguistics 10: 257–277. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-linguistics-031422-124743

Further Reading:

📚 Books & Media

New (and old) books and media touching on language and linguistics.

I discovered a new book coming out in April that looks like a great read: Rare tongues: The secret stories of hidden languages. It focuses on rarities in the world’s languages and how linguistic diversity is declining. I’ll definitely be getting a copy of this one for myself and try to do a review for y’all:

That’s all for this week! I had to delay my work on my special thank-you post for my first 1,000 newsletter subscribers in order to write about Trump’s official English order while it was still in the news cycle, so I’ll be turning my attention back to that project this week. I’m excited to share the result with you!

Thanks for reading, and have a wonderful week!

~ Danny

If you enjoyed the post, consider becoming a supporter to get even more!

✨ Perks ✨

📝 early access to chapters of my book, Universal: The diversity of language and the unity of the human mind

➕ bonus articles/videos

👀 early access to articles/videos

💝 support my mission to educate the public about the science and diversity of language!

🚫 Errata

Corrections and clarifications.

In my article on Trump’s official English policy, I wrote:

This is despite the fact that the number of people speaking languages other than English in the United States has tripled since 1980, from 1 in 10 to 1 in 5.

The tripling refers to the absolute number of speakers, not the ratio. The corrected version says:

This is despite the fact that the number of people speaking languages other than English in the United States has tripled since 1980, from 23.1 million (1 in 10) to 67.8 million (1 in 5).

The Amazon and Bookshop.org links on this site are affiliate links, which means that I earn a small commission from those companies for purchases made through them (at no extra cost to you).

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!