The sad passing of Kanzi, penguin etymology, and what “fixin’ to” / “finna” mean

Here's what happened this week in language and linguistics.

Happy weekend! Enjoy one of my favorite silly comics to kick off this week’s digest:

Welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Dispatch, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics.

Apologies that this issue of the digest comes late this week. I’m discovering that breaking news relating to language (Trump’s official English order, Kanzi’s death, semantic confusion about tariffed penguins, etc.) has a dilatory effect on my writing schedule for other content! I’ll continue to aim for a consistent Thursday morning release for now, but I may adjust the schedule in the future. I’m only 3 months in to writing this weekly digest, so I’m still learning what works best! Thanks for your patience with my somewhat erratic posting schedule as I find my rhythm with my research and writing process.

On the upside, I produced a ton of content for you to explore this week! Hope you enjoy!

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week's content from Linguistic Discovery.

two pronunciations of ⟨w⟩

I saw a fun post about the pronunciation of ⟨w⟩ on Threads and decided to reply:

My response on Threads is here, but here’s a more detailed explanation:

English does have two pronunciations of the letter ⟨w⟩!

One is /w/, the voiced labiovelar approximant. This is the sound most people think of when they think of /w/, and is the first sound in the word witch.

The other is /ʍ/, the voiceless labiovelar fricative, which is more or less just the voiceless version of /w/, meaning your vocal folds aren't vibrating. This is why /ʍ/ is described as "breathy" or "whispered”. For the people that use this sound, it’s the first sound in the word which.

Stewie Griffin famously uses the /ʍ/ pronunciation in the phrase Cool Whip:

Historically, the majority of English speakers made this distinction, and the two sounds were even written differently: ⟨w⟩ vs. ⟨wh⟩ in Middle English. (Old English used ⟨hw⟩ instead, like the first word of Beowulf, hwæt, which became Modern English what.)

Many words spelled with ⟨wh⟩ today were once pronounced with the voiceless /ʍ/.

Today however most American English speakers just use /w/. /ʍ/ has been lost except for in the speech of some older speakers, especially in the South. Most varieties of British English, however, retain the distinction.

fixin’ to / finna

The phrase fixin' to means that the event will happen in the near future. Think of it as parallel to going to, but with a slightly more restricted meaning.

And just like going to can be pronounced as gonna whenever it's functioning as a type of grammatical aspect, fixin' to is pronounced by many people as finna, especially in African American English.

This first map shows that fixin’ to is used primarily by speakers in the southeastern United States. It shows the average acceptability of fixin’ to sentences on a scale of 1–5 among survey participants.

The second map shows the ratio of people who pronounce it as fixin’ to (purple) and finna (green). The other maps show the uncombined frequencies.

The first map is from the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project, and the others from linguist Jack Grieve. Read all about the fixin’ to construction at the Yale Grammatical Diversity Project:

fixin’ to (Yale Grammatical Diversity Project)

📰 In the News

Language and linguistics in the news.

Kanzi the bonobo dies

Kanzi the bonobo, who researchers taught to use symbols to communicate and stone tools, has died at the age of 44.

I wrote a long tribute to Kanzi, explaining his contribution to the field of linguistics and why his incredible linguistic abilities matter to the field:

Kanzi (1980–2025)

In the early 1980s, a team of researchers led by Sue Savage-Rumbaugh at Emory University’s Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center were struggling to teach a bonobo named Matata how to use a symbolic picture system called Yerkish to communicate. Each symbol, called a

Here are some interesting YouTube videos demonstrating Kanzi’s abilities:

Press Coverage

Kanzi the bonobo, who learned language and made stone tools, dies at age 44 (Scientific American)

RIP Kanzi, the bonobo who mastered language and Minecraft (Gizmodo)

Remembering Kanzi, the bonobo who helped us understand humanity (Iowa Public Radio)

penguins

A recurring theme on the internet this week was to joke about how the penguins of Heard Island & McDonald Islands, Australian territories near Antarctica, were hit with a 10% tariff by Trump. (No people live on these islands, just penguins.)

This apparently caused some confusion among French speakers because a pingouin in French is not technically the same animal as a penguin in English. A follower called upon me to explain, so I indulged:

It turns out the semantics and etymology of penguin is actually rather surprising! You can read all about it here:

The etymology of “penguin”

The penguins of Heard Island and McDonald Islands, Australian territories near Antarctica, have been slapped with 10% tariffs by Trump. The internet is reeling with the injustice of it all, and I’ve been summoned to bring all my linguistics skills to bear in aiding the hapless penguins:

zeugma / syllepsis

The New York Times had a great example of zeugma / syllepsis in one of its headlines this week:

A zeugma is when two different parts of a sentence utilize two different meanings of one word in the sentence (without repeating that word).

The most repeated example is “He took his hat and his leave”. In that sentence, two different senses of take are being evoked.

What I love about zeugma is that they demonstrate how contextualized the meanings of words are. Every word has a web of interconnected meanings, some of them only distantly related after centuries of semantic shift, but different linguistic contexts will highlight different senses of the word.

zeugma comes from the Ancient Greek ζεῦγμα zeûgma, literally ‘a yoking together’, whereas syllepsis is from the Ancient Greek σύλληψις súllēpsis ‘a taking together’.

(Hat tip to my dear friend and medieval scholar George Greenia for teaching me this fun construction many years ago.)

iOS 19 to support live translation

Bloomberg reports that iOS 19 on iPhone will enable live translation using Apple AirPods. From Apple Insider:

If an English speaker with AirPods is listening to a person speaking in another language, such as Spanish, the iPhone will detect the audio of the Spanish speaker and translate it into English. The English translation will then be played via the AirPods.

The English speaker's response is said to be translated and played in Spanish via the iPhone speakers. The process allegedly utilizes the Translate app and is tied to the iOS 19 update.

Apple plans AirPods feature that can live-translate conversations (Bloomberg)

Your existing AirPods could gain a new live translation feature in iOS 19 (Apple Insider)

It’s worth noting that Apple’s Translate app only has 7.6k reviews, with an average rating of 2.3/5, as opposed to the Microsoft Translator app, which has 159k reviews and an average rating of 4.8/5. So while I personally think this is a cool idea with a lot of potential utility, I’m not going to hold my breath hoping it’ll be very good.

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

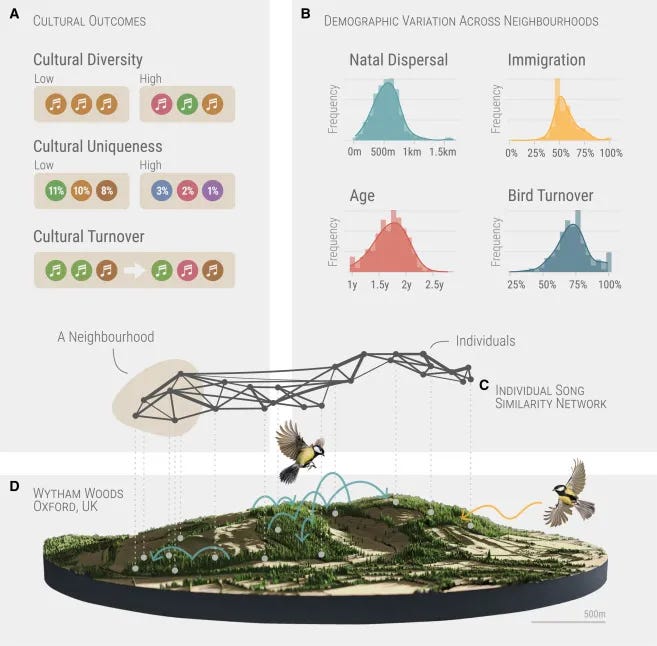

Dialect diversity in birdsong

Some types of birds have local dialects of birdsong, and those dialects are influenced by long-range interaction with birds of other regions, according to a paper in Current Biology this month. Here’s a key quote from the Washington Post article:

Results showed that dispersal within the population — referring to how far the birds traveled from where they were born to where they settled down to breed — “homogenises song culture” over time and slows down the pace of change. Immigrant birds also were shown to adopt local songs and learn more songs overall, helping to enrich the “musical scene,” researchers said.

By contrast, “homegrown” songs in areas where birds stay close to their birthplace tend to stay unique, similar to the way in which isolated human communities can develop distinct local dialects over time, the team found.

Birds can change their tunes as their populations evolve, researchers find (NPR: All Things Considered)

Turns out birdsongs evolve with time and age—just like human music (Washington Post)

Merino Recalde et al. 2025. The demographic drivers of cultural evolution in bird song. Current Biology 35: 1–10. DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2025.02.016

Bonobos point more for ignorant than knowledgeable social partners

I referenced this in my article about Kanzi, but it’s worth mentioning separately too because the study was only just published in February. (It may have been the last research study Kanzi participated in. 😢) Here’s an excerpt from my article:

One experiment demonstrates Kanzi’s grasp of theory of mind well: Researchers would hide a grape under a cup, then ask Kanzi (or the other bonobos in the experiment), “Where’s the grape?” If the researcher was present when the grape was being hidden, the bonobo often didn’t respond to the request. But if the researcher had been absent for the grape-hiding, the bonobo would more often quickly point to the right cup. The results suggest that the bonobos had some understanding of the researcher’s state of knowledge about the location of the grape.

Reporting: Bonobos realize when humans miss information and communicate accordingly (Phys.org)

Original Research Study: Townrow, Luke A. & Christopher Krupenye. 2025. Bonobos point more for ignorant than knowledgeable social partners. PNAS 122(6). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2412450122

📃 This Week’s Reads

Interesting articles I've come across this week.

Because I posted about Spoonerisms the other week, many people messaged me about the New York Times’ Strands puzzle for March 17. The theme for the day’s puzzle was “Sounds switching”, the spangram was “Spoonerisms”, and, hilariously, the puzzle actually included some real Spoonerisms:

blushing crow ← crushing blow

bedding wells ← wedding bells

stricken chips ← chicken strips

I got a kick out of that 😅

CNET explains the puzzle in more depth:

Other articles from the week:

Donald Trump thinks some accents are ‘beautiful,’ but what makes them so? (The Conversation)

📚 Books & Media

New (and old) books and media touching on language and linguistics.

I watched the first season of Wolf King last week, and their use of were- as a prefix struck me as really interesting! So I recorded a short video about it. (I’ll probably have a written version of this soon too.)

Werewolves, werelions, werebears, and & other werebeasts: The linguistics of Wolf King (Linguistic Discovery on YouTube)

While doing research about Kanzi I found this great kids book about him!

🗃️ Resources

Maps, databases, lists, etc. on language and linguistics.

For language lovers like me, I think it’s really helpful to know how to pronounce words in other languages, even if you aren’t learning to speak them. Plus I’m sure speakers appreciate it when I don’t butcher their language. So it was nice to see this guide to French pronunciation from the Rosetta Stone blog recently:

Your ultimate French pronunciation guide (Rosetta Stone Blog)

Another excellent resource for French pronunciation is the little book Exercises in French phonics. It was published in 1981 but I still found it helpful 45 years later.

Thanks for reading! Let me know how I’m doing with the newsletter and how I can improve by emailing me here!

~ Danny

The Amazon and links on this site are affiliate links, which means that I earn a small commission from Amazon for purchases made through them (at no extra cost to you).

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!