When the Spanish began their conquest of Mesoamerica in 1519, the dominant language in the region near modern-day Mexico City was Aztec—or as it’s called in the language itself, Nahuatl (pronounced in English as /ˈnɑ.wɑ.təl/ and in the language itself as /ˈnaː.wat͡ɬ/). The -tl at the end of that word is a suffix added to the ends of stems to create nouns. The root of the word is nāhua- ‘audible, intelligible, clear’. So nāhuatl literally means ‘speaking intelligibly’, referring to the Nahuatl language. The variety of Nahuatl spoken at the time of Spanish conquest is known as Classical Nahuatl. There are still about 1.7 million Nahuas who speak the language today, although the language has changed significantly over the last 500 years and has started to diverge into distinct languages.

Prefer a video version of this post? Watch here:

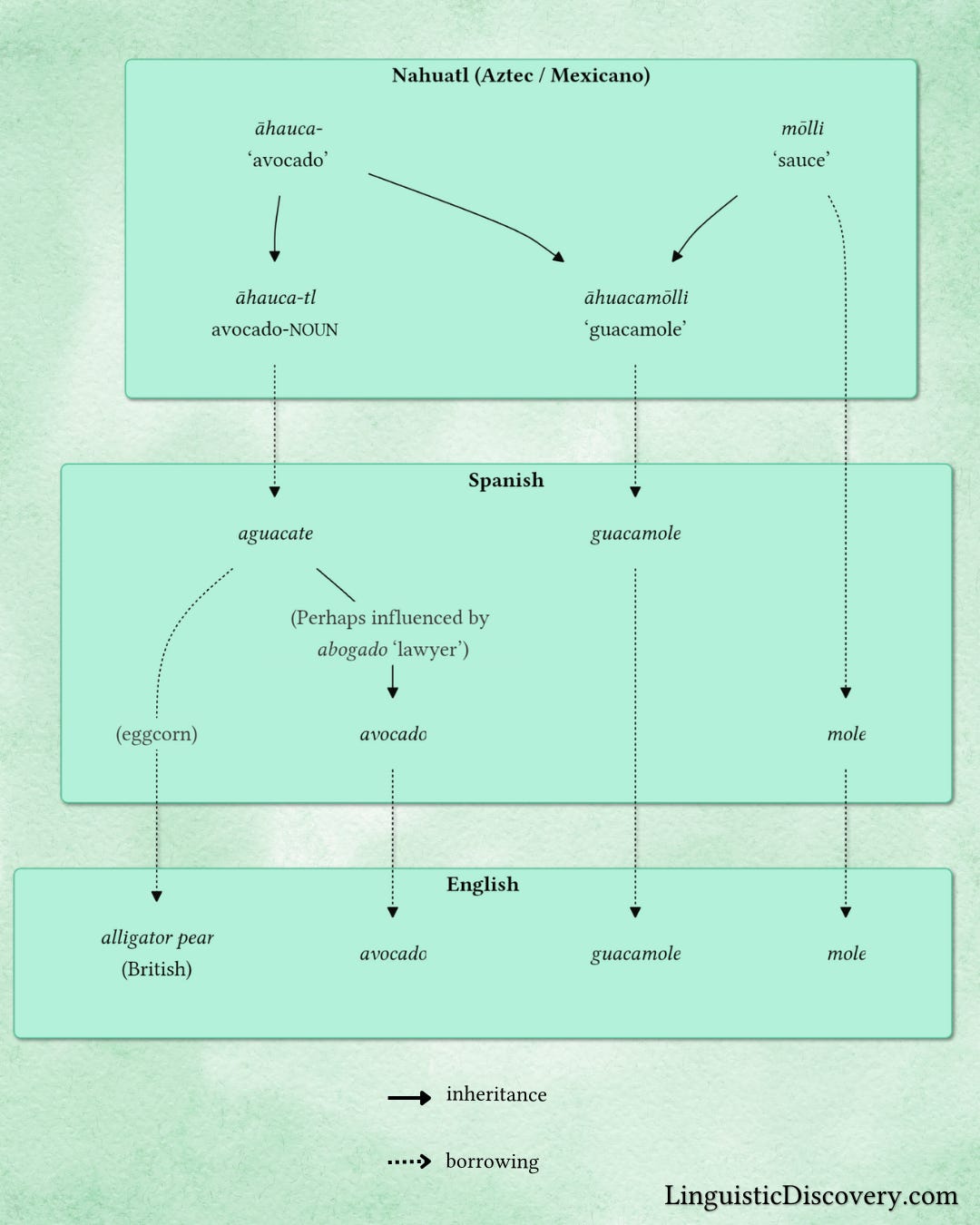

Now, the root meaning ‘avocado’ in Nahuatl is āhuaca-, and the suffixed version of that root is āhuacatl. The Spanish borrowed this word as aguacate, a folk etymology based on parsing the first part of āhuacatl as the Spanish word agua ‘water’. aguacate remains the word for ‘avocado’ for many Spanish speakers today.

However, some Spanish speakers, perhaps confusing aguacate for the somewhat similar-sounding abogado ‘lawyer’, began pronouncing the word as avocado, and that was the version later borrowed into English.

Many people mistakenly believe that avocado originally meant ‘testicle’ in Spanish, but this has the history reversed. The Franciscan priest Alonso de Molina includes both ‘avocado’ and ‘testicle’ as definitions for āhuacatl in his 1571 dictionary of Nahuatl, but the ‘testicle’ meaning is just a euphemism (since avocados resemble testicles and often grow hanging in clumps of two).

The original Spanish word aguacate itself underwent another folk etymologization among some English speakers, who believed that they were hearing the word alligator instead of aguacate—a plausible interpretation given that avocado skin does resemble alligator skin. Some British English speakers today still call avocados alligator pears (because they’re similar to pears in shape).

Lastly, let’s return back to Nahuatl for a moment: Nahuatl also had a word mōl- ‘sauce’. When the noun suffix is added to a stem ending in /l/ it becomes -li rather than -tl, yielding the noun mōlli. That was borrowed by the Spanish as mole, and later by American English speakers as mole as well. But Nahuatl combined those two roots, āhuaca- and mōl-, into a single word āhuacamōlli ‘avocado sauce’ (again with the -li version of the noun suffix added). When the Spanish borrowed this word, it became guacamole, and American English speakers borrowed the word guacamole from Cuban Spanish in the early 1900s.

So that’s just a quick sampler of a few Nahuatl words that have found their way into English. Now that you know about the -tl / -li ending (which often lost its final /ɬ/ when borrowed into Spanish or English), it’s pretty easy to spot others as well: chipotle, chocolate, coyote, axolotl, tomato are a few more.

You can see an etymological flowchart of the history of avocado and guacamole below.

📖 Recommended Reading

📑 Sources

Diccionario de la lengua española [Dictionary of the Spanish Language]

Etymonline

Launey. 2004. The features of omnipredicativity in Classical Nahuatl

The Amazon links in this post are affiliate links, which means that I earn a small commission from Amazon for purchases made through them (at no extra cost to you).

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!

アボカドが大好きです!A mi me encantan los aguacatesI love avocado and I love language. Thanks for the informational piece!