Is AI changing language? Plus new evidence of a “language protein”

A recent article argues that AI is wrecking language, and new research has found a "language protein". Here's what happened this week in language and linguistics.

Happy Friday! Or Lover's Day as I sometimes jokingly call it, since the name comes from the Old English Frigedæg ‘Frigga’s Day’, Frigga being the Germanic goddess of love. The name is a calque (loan translation) of the Latin phrase diēs Vēneris ‘Venus’ day’.

On the other hand, the Proto-Indo-European root of Frigga is *pri- ‘love’, which also yielded words like friend and free and freedom. So sometimes it’s fun to say that Friday etymologically could also be called “Free Day”, which I think is appropriate since it’s the day you’re finally free from work.

In any case, welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Dispatch, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics.

📋 Contents

📢 Updates

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

📰 In the News

🗞️ Current Linguistics

📃 This Week's Reads

📑 References

📢 Updates

What’s new with me and Linguistic Discovery.

Joining the Babel panel

A fun update from me this week: I’ve been asked to join the advisory panel for Babel: The Language Magazine, to which I happily agreed. You may have seen me post excerpts from the magazine from time to time. In fact, my post the other day on loanwords in Hawaiian was directly inspired by a section of one of their recent articles. I think they do a great job with their longform writing, and fill an important niche in the magazine space. I don’t know any other magazine devoted to language and linguistics. It’s great to see that it’s been as successful as it has been over the years, since it’s bringing linguistics to a wider audience. I’m excited to help guide the direction of the magazine going forward!

Three ways to read/watch Linguistic Discovery

You can now read Discovery Dispatch (and/or the World of Words newsletter) on your platform of choice:

Personally, I recommend the Linguistic Discovery website because it’s got the best formatting. But you’ll get the same articles, videos, and bonus content no matter which platform you use. So feel free to unsubscribe from this one and subscribe on your preferred platform.

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week's content from Linguistic Discovery.

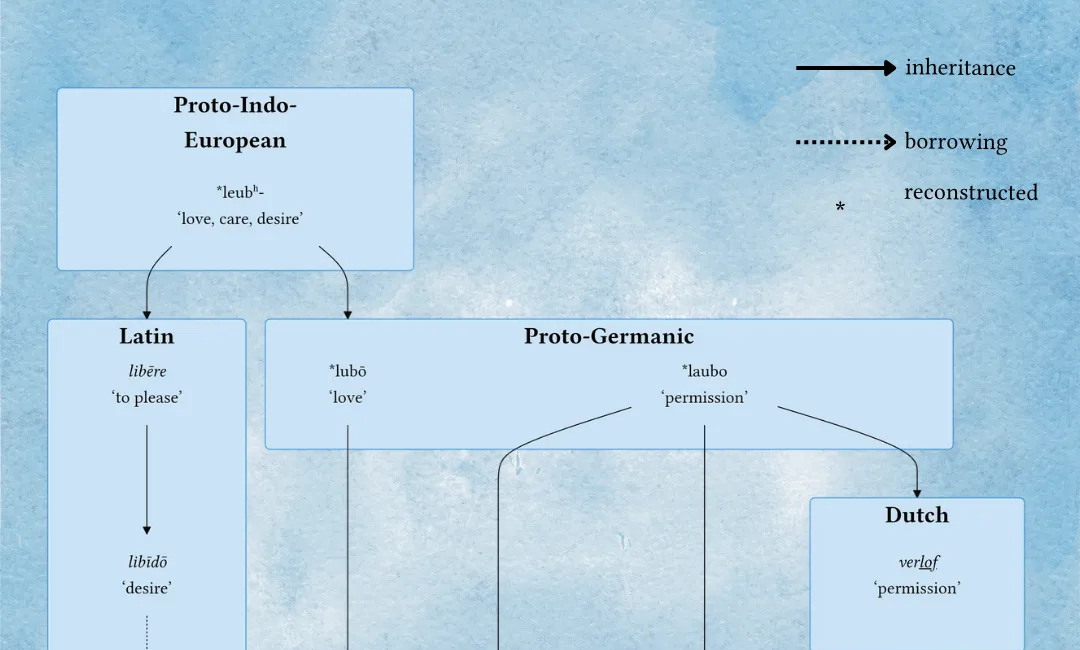

For Valentine’s Day, I explored the etymology of love and its reflexes in English:

The linguistic history of "love"

The Proto-Indo-European language had a word *leubʰ- ‘love, care, desire’, and today I’m going to tell you all the ways this word has come down to us in English 6,000 years later—a kind of “reverse etymology”.

The Hawaiian language only has 8 consonants. So what happens when it borrows words with other sounds?

Hawaiian only has 8 consonants—What happens when it borrows words with other sounds?

The Hawaiian language only has 8 consonant sounds (phonemes), making it one of the smallest consonant inventories of any language in the world. (The smallest consonant inventory goes to Rotokas with only 6!) (Gordon 2016: 44)

📰 In the News

Language and linguistics in the news.

Sadly, two distinguished linguists passed away this week—Sally McLendon and Nancy Dorian. Sally McLendon worked with indigenous communities and languages in North America, and most especially Northern California. Nancy Dorian is best known for her work on language shift and language preservation, working especially with Gaelic.

You can read their obituaries from the Linguistic Society of America here:

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

A few interesting studies were publicized this week, which I’m surprised aren’t getting more media uptake:

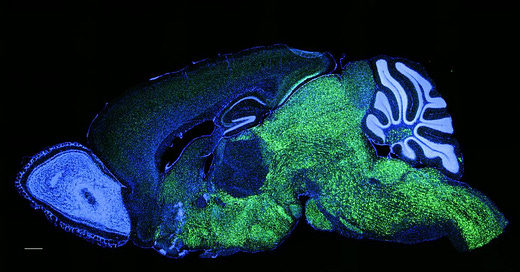

First, a study in Nature Communications found a protein called NOVA1 that is unique to humans and appears to be linked to vocalizations:

A single protein may have helped shape the emergence of spoken language (Rockefeller University)

The study has echoes of the research identifying FOXP2 as the “language gene”. Nativists get excited about this kind of research because they think it lends credence to the idea that language is an innate genetic adaptation rather than learned. However, such research is perfectly compatible with theories that assume language is learned as well. Cognitive linguistics holds that the cognitive capabilities we use to learn language are the same ones we use to learn all sorts of other things—pattern recognition, theory of mind, hierarchical mental representations, etc. In other words, language is domain general; there isn’t a component or set of functions in the brain that evolved specifically for language.

For cognitive linguists, then, the difference between animals and humans isn’t language per se; it’s that humans have a different set of cognitive capabilities, and these capabilities enable us to learn language, among many other things. So it’s no surprise that there are aspects of our genetics which are both unique to humans and relate to language, because language uses a variety of different cognitive skills, some of which are unique to humans. They didn’t necessarily evolve for language, but they enable language. What would be a surprise is if we discovered a genetic difference between humans and other animals that only affected language.

Next, a study found that macaques appear to associate spoken words with pictures:

Macaques appear to associate spoken words with pictures (Popular Science)

The reason this is cool is because there’s no inherent connection between an image and a word—it’s arbitrary and something that has to be learned. This is unlike most associations in the animal kingdom, where there’s some sort of iconic connection between the signal and the thing itself. A lion’s roar is, obviously, inherently associated with lions. But the word lion is arbitrary (as evidenced by the fact that the word for ‘lion’ is different from language to language).

But the especially neat part about this study is that, while the macaques struggled to associate words with pictures at first, they quickly got better at it, acquiring subsequent associations much more quickly. This shows that macaques have the cognitive ability to make arbitrary and possibly symbolic associations between sounds and things, independent of whether they actually learn to use that ability. But once they do learn it, they quickly become efficient at it. This is similar to how humans learn language. Infants first have to grasp the idea of a symbolic link between words and concepts, but once they do, language acquisition proceeds at a remarkable pace.

Finally, a study published in the Journal of Neuroscience shows that elements of birdsong are context dependent, similar to how sounds in human language are pronounced differently depending on the sounds around them. For example, the /n/ in input is often pronounced as [m] in rapid speech, in anticipation of the /p/ that follows it. This is because /p/ is a bilabial sound (pronounced with both lips), so the /n/ changes its place of articulation to become bilabial as well.

📃 This Week's Reads

Interesting articles I've come across this week.

There were some neat articles in The Conversation this week. (I always really enjoy The Conversation, because their articles are written by scholars/researchers with the aid of an editor who helps them convey their ideas in ways that are accessible to a general audience. I’ve got an article myself, in fact.)

What happens in the brain when there’s a word ‘on the tip of the tongue’?

How we’re recovering priceless audio and lost languages from old decaying tapes

How Oscar-nominated screenwriters attempt to craft authentic dialogue, dialects and accents

The Babbel blog has an article about how learning a language benefits brain health:

And not to be too impolitic, but here’s a sensationalist worrymongering piece from Forbes claiming that AI will reduce our vocabulary and introduce fake non-human words:

There are two things you should keep in mind whenever you read something about how technology or the internet is affecting language:

Children don’t learn language from writing, videos, or the internet.

Children aren’t exposed to writing as infants. Children don’t typically learn to read until ages 4–7, long after the core of their linguistic abilities are already in place. True, children don’t become fluent until about age 7–8, and people continue to expand their vocabulary and sometimes even their grammar throughout their lives, but the impact of those later changes is relatively minor. So claims that various forms of writing on the internet—like that produced by generative AI—are having drastic effects on language are simply unrealistic.

More importantly, children need social interaction in order to learn a language. They cannot learn their first language from TV or streaming video services. In one case, deaf parents gave their hearing son lots of exposure to TV and radio in hopes that he would learn English, but this didn’t happen. He did however learn American Sign Language effortlessly, because that was the language used in his immediate social environment. (Moskowitz 1991)

The point here is that by the time a child is old enough for reading and digital media to have a major impact in their life, it’s too late for that impact to amount to anything more than some new vocabulary words.

Vocabulary is always changing.

Every time a new language-related technology is introduced, people make sensationalist claims that it will change (usually ruin) language. This is part of a broader disposition that most people have which resists language change. The majority of people think that the way they grew up speaking is best, and any further changes are bad. So if they think that certain technologies are introducing or accelerating language change, they’re naturally resistant to it. Socrates himself objected to the use of writing (which is a technology) because he said it would weaken one’s memory. (This is why all his philosophy comes down to us in the form of dialogues written down by his student Plato.)

But languages are always adding new words and changing their meanings, regardless whether those words/meanings come from writing, books, TikTok, or AI. And it is highly unlikely that more recent technologies are adding or changing words faster than in the past. This perception probably stems from older generations feeling overwhelmed by new vocabulary that didn’t exist when they were young. But in every generation you can find adults writing about the flood of new slang/vocabulary from the youth. This is hardly a new phenomenon.

The medium by which new vocabulary is introduced may be changing as technology changes, but the process of lexical expansion is not fundamentally different from one generation to the next.

Frankly, I find vocabulary change pretty boring (except in cases of extensive borrowing in language contact, which sometimes yields cool things like mixed languages). What would be a big deal is if a new technology somehow changed the grammar of a language, but I’m not even sure how that would be possible.

Irritatingly, the author concludes by saying maybe the homogenization and simplification of language isn’t a bad thing, since it would foster global communication. There are many more fallacies I could address there too, but since that wasn’t his main point and this section of the digest is already long enough, I’ll leave that rant for another day.

Some other cool articles I came across this week:

People have been saying “ax” instead of “ask” for 1,200 years (Smithsonian Magazine)

Unraveling the complexities of accent identification (ScienMag)

This article includes a discussion of how language shapes our perceptions of others too:

The rich mosaic of sounds and rhythms in Indian-accented English can confuse the American ear (IndiaCurrents)

Okay, I’m off to participate in a panel for Career Linguist talking about my career advice for linguists! More on that next week. Feel free to let me know what you thought of this issue! Thank you for reading, thank you for being a supporter, and I hope you have a wonderful week!

~ Danny

📑 References

Moskowitz, b. 1991. The acquisition of language. In W. Wang (ed.), The emergence of language, pp. 131–149. W. H. Freeman.