Gestures can counteract subtle stereotypes introduced by language

This week I discuss the growth of science communication in linguistics, plus how simple gestures can counteract subtle linguistic biases.

When I first started Linguistic Discovery on TikTok back in December 2020, I wasn’t sure how to explain what it was I was doing or describe myself. “influencer” didn’t seem like a good fit, since that term typically brings to mind people who do lots of brand deals and lifestyle vlogs rather than educational videos. I didn’t mind “intellectual influencer” or “thought leader” (despite the cliche jargon), except that my content doesn’t really try to convince people of anything or advocate for some particular idea (other than just not being a prescriptivist about the way people talk). I see my task as primarily one of educating rather than convincing. The term “content creator” felt better, since I was making educational content, but still didn’t quite capture it.

Then I learned the term science communication—communicating findings and knowledge from scientific fields in an accessible way to general audiences.

Science communication is nothing new, of course. As early as 1987, Geoffrey Thomas & John Durant published a paper titled “Why should we promote the public understanding of science?”, in which they perspicaciously observed that science communication has the benefit of drawing more people into scientific fields. I think this is especially true of linguistics, which most people never hear of in school. I’d wager that a majority of people are exposed to linguistics for the first time through the efforts of linguistics communicators like myself. And even online science communication on social media has been around for a while—just look at YouTubers like Hank Green. But the term has become more established—and the community larger—in recent years. Since starting Linguistic Discovery, I’ve discovered an entire cadre of content creators like me whose goal is to disseminate scientific knowledge in accessible ways.

Moreover, academia writ large is placing increasing importance on public outreach. Most research grant proposals, for example, now require a discussion of potential “broader impacts”. Science communication has gone from being outright discouraged to a legitimate activity within academia.

Today I call myself a science communicator, and a linguistics communicator specifically. And like in the rest of academia, there is a growing recognition within the field of linguistics of the utility and worth of activities like mine. The Linguistic Society of America (LSA), for example, now runs a yearly 5-Minute Linguist competition (I believe inspired by a book of the same name), which the society describes as follows:

The Five-Minute Linguist is a high-profile event which features LSA members giving lively and engaging presentations about their research in a manner accessible to the general public. […] The goal of this event is to encourage LSA members to practice presenting their work to a broad audience and to showcase outstanding examples of members who can explain their research in an accessible way.

The 5-Minute Linguist has indeed become a high-profile event and one of the highlights of the yearly conference.

There’s now also an entire conference dedicated to linguistics communication, called LingComm, that’s held online every other year, and was originally conceived of and organized by Gretchen McCulloch & Lauren Gawne of the excellent Lingthusiasm podcast. I participated in a LingComm panel discussion about social media for LingComm in 2023, and will be doing so again in 2025.

A group of scholars is also organizing a special panel at next year’s American Association of Applied Linguistics (AAAL) conference on using social media to communicate linguistics with broader audiences. Fellow linguistics communicator Dr. Lizzy Hanks (TikTok | Instagram) asked me to co-present on the panel with her, and we’re in the beginning stages of coauthoring a paper together on the topic.

So it’s been great to see the growing appreciation for science communication and the type of work I do within academia. And I certainly never expected that I’d be successful enough at it that others would want to hear my perspective on it! I’m very excited to participate in both LingComm 2025 and AAAL 2026.

And all that’s just a long-winded way to say that’s what I’ve been working on this week! Welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Dispatch, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media. Here’s what happened this week in language and linguistics.

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week's content from Linguistic Discovery.

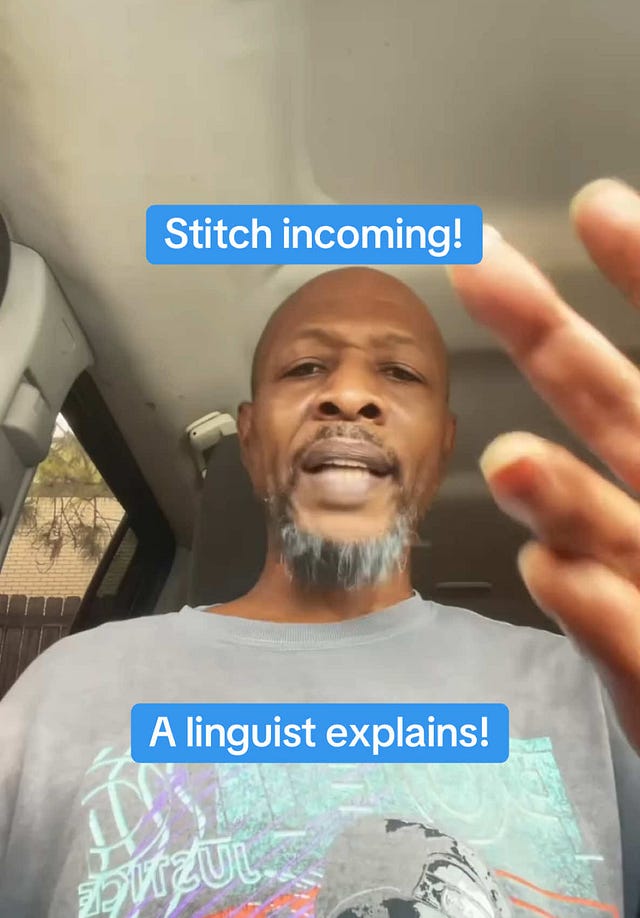

The other day on TikTok I came across a great example of tip of the tongue phenomenon, also called lethologica, where a person struggles to remember a word or phrase. Since videos of these “brain glitches”, as they’re often tagged as on TikTok, are both hilarious and incredibly linguistically interesting, I immediately liked the video and made a short reply to it. Then, the TikTok algorithm being the TikTok algorithm, it fed me even more videos of these “brain glitches”. The result is I’ve now got three videos about tip of the tongue phenomenon for your viewing pleasure. I’ll include both the TikTok links and YouTube links below for people who don’t have TikTok.

What’s remarkable about tip of the tongue events from a linguistic perspective is that people can recall specific features of a word/phrase without recalling the entire word/phrase. They might remember its syllabic structure, its prosodic structure (such as which syllables are stressed), and the place or manner of articulation of certain consonants, but not all the details. People often use semantically related or associated words to help them remember the details of the word, as you’ll see in the videos. For example, in the guacamole video, you’ll see the woman slow down and try to fit the word into the collocation “a cup of …”. The cup of coffee case is also interesting because it shows how tip of the tongue events can occur with entire phrases, not just words. It’s not until the man slows down and thinks about the individual pieces of that phrase (rather than trying to produce it as a holistic stretch of speech) that he gets it.

guacamole

Original Video:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

My Response:

bathroom vanity

Original Video:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

My Response:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

cup of coffee

Original Video:

Tiktok failed to load.

Tiktok failed to load.Enable 3rd party cookies or use another browser

My Response:

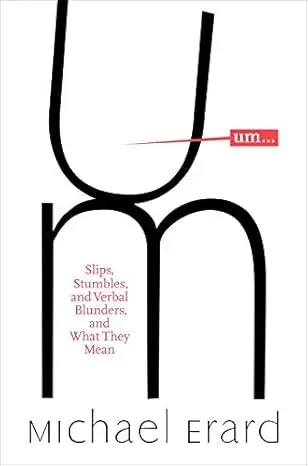

Further Reading

I recommended this last week too, but if you’d like to learn more about these kinds of speech errors, here’s my rec:

The video about guacamole prompted one follower to ask where that word comes from, so I decided to oblige:

guacamole = avocado mole

When the Spanish began their conquest of Mesoamerica in 1519, the dominant language in the region near modern-day Mexico City was Aztec—or as it’s called in the language itself, Nahuatl (pronounced in English as /ˈnɑ.wɑ.təl/ and in the language itself as /ˈnaː.wat͡ɬ/). The

Here’s the complete etymological tree for guacamole and its related words in English:

After the word āhuacatl was borrowed into Spanish as aguacate, some speakers altered the pronunciation of the word to avocado, perhaps influenced by the word abogado ‘lawyer’. Most speakers still say aguacate, however.

Many people think that avocado originally meant ‘testicle’, but this has the history backwards. The original meaning was ‘avocado’, and then the word got used as a euphemism for ‘testicle’.

In British English, the fruit is also sometimes called an alligator pear, where alligator is an eggcorn for aguacate (perhaps because its skin looks like alligator skin), and it’s called a pear because of the similarity in shape.

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

Gestures can counteract subtle stereotypes introduced by language

One of the most important discoveries in linguistics of the past century is just how much language relies on mental models or image schemas. This was popularized in George Lakoff’s famous book, Metaphors we live by (Amazon | Bookshop). For example, English speakers conceptualize time as being linear, with the past being behind us and the future in front of us. In the Aymara language, however, the past as conceptualized as being in front of the speaker, and the future behind (Science).

Even the fact that words are produced one after another has subtle effects on how we interpret sentences. The actions in the sentence “I brushed my teeth and went to bed” could be interpreted as happening in either order or even simultaneously, but the most natural intention and interpretation of conjoined actions is that they happened in sequence—first brushing the teeth, and then going to bed.

Once these mental models become ensconced in language, it can be difficult—but not impossible—to escape them. However, new research shows that the addition of a simple gesture can be enough to overcome those preexisting mental models built into language.

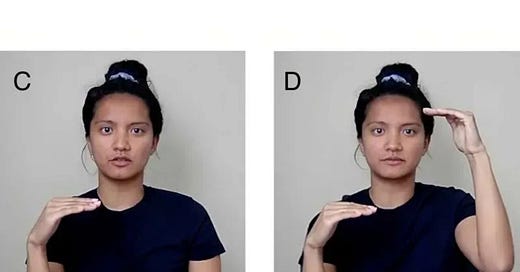

Sentences like “Girls are as good as boys at math” are similar to sentences with conjoined actions like the example above in that you could interpret the sentence as saying that girls and boys are equally good at math, but the most natural interpretation is that boys are the standard or reference group against which girls are judged. The linguistic construction imposes a mental model where the groups are of unequal status. This has real effects on a person’s beliefs and attitudes: in this study, researchers show that simply using the “as good as” construction made children who heard the sentence much more likely to say that boys—the standard or reference group—were better than girls at the invented action of “yuzzing”. (The researchers used an invented word to avoid any existing stereotypes the children might have had. So even though the kids had no idea what “yuzzing” was, they still had clear judgments that boys were better than girls at it.)

However, by merely making a gesture with two palms held at equal height at the same time the researchers said that “girls are as good as boys at yuzzing”, the statistical bias towards boys disappeared entirely. Students who saw the equal gesture showed no favoritism towards either boys or girls when asked who was better at “yuzzing”.

So this is a neat study because it shows both how pervasive and how fragile our mental models are at the same time. While language can indeed bias people towards certain ways of conceptualizing the world, those linguistic biases can be quite easily overcome.

Reporting: Simple physical gestures can counteract stereotypes introduced by subtle linguistic cues (Phys.org)

Original Research Article: Gesture counteracts gender stereotypes conveyed through subtle linguistic cues (PNAS)

📃 This Week’s Reads

Interesting articles I've come across this week.

Haaretz has a fascinating article in their Archaeology section this week about the loss and revival of names for fish in Hebrew. Sounds boring perhaps, but it’s actually a great encapsulation of the entire process of language loss and revitalization. It discusses different strategies that language revivalists used to fill out fish-related vocabulary while revitalizing Hebrew, and how some of those strategies worked, others failed fantastically, and others brought about changes they didn’t expect. A surprisingly interesting read.

Further Reading

🗃️ Resources

Maps, databases, lists, etc. on language and linguistics.

While doing research for my article on Trump’s official English order the other week, I came across this neat map produced by the government of Canada’s Northwest Territories, showing the regions where the official languages of the territories were spoken historically:

Further Reading

That’s all for this week! Let me know what you thought of this week’s issue and/or how you think I could improve this digest! Have a good week!

~ Danny

The Amazon and Bookshop.org links on this site are affiliate links, which means that I earn a small commission from those companies for purchases made through them (at no extra cost to you).

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!