The way we read in our first language influences how we read in other languages

Also this week: AI models can now analyze language as well as humans + The first monolingual Irish dictionary is published

Welcome to this week’s edition of the Discovery Digest, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics!

📢 Updates & Announcements

Announcements and what’s new with me and Linguistic Discovery.

🎆 One year of Linguistic Discovery

2025 was the official first year of the Linguistic Discovery newsletter! I soft-launched the newsletter with a few articles in late 2024, then published my first weekly digest in late January 2025. What a year it’s been! Here are some quick stats from the year:

Digest Issues Published: 42

Articles Published: 28

Subscribers: 6,456

Reads: 141,881

Top Articles

At various points throughout the year, the Linguistic Discovery newsletter was also featured as a Rising Newsletter in the Science category on Substack, reaching #33 at its peak!

Read more about my thoughts on 2025 and what’s coming next for 2026 in this issue of the newsletter:

2️⃣0️⃣2️⃣6️⃣ What’s changing (or not changing) in 2026

I’m making a few changes to the newsletter in 2026:

I’ll continue publishing this digest of the latest news and research in linguistics. Many of you told me in your responses to the reader survey how much you value this digest, so I’ll keep it going! However, the digest will probably be shorter going forward, if only because I’ve now worked through my backlog of content for it. (There simply isn’t that much new linguistics stuff to talk about each week!) I may also experiment with a biweekly posting schedule (every other week).

I’ll aim to publish one new longform article each week. Each week I’ll publish an article about grammatical diversity in the world’s languages, how language works, explainers of terms and concepts in linguistics, or profiles of specific languages. You told me through the reader survey that you’re especially interested in the first two topics, so most of the articles will be in those areas.

New publishing schedule. You also told me in the reader survey that you’re a bunch of morning birds! A majority of you prefer to have the newsletter delivered in the early morning before work, so that’s what I’ll do: I’ll aim to have the newsletter in your inbox by the time you wake up (probably 4am ET). The weekly digest will now be delivered on Tuesdays, and articles will be delivered on Saturdays. (These times/schedules are subject to change if I notice significant changes in open rates etc.)

Digest: Tuesdays @ 4am ET

Articles: Saturdays @ 4am ET

I’m starting a book project! And paying supporters will get early access! The working title is The Linguarium: A field guide to the world’s languages. The book is a tour of the diversity of the world’s languages, from click languages to reconstructed languages to whistled languages to secret languages to the language of thought to animal languages to the very first human language, and many more. I’ll syndicate the book so that each section/chapter is an issue of the newsletter. But because I want to pitch the book to a traditional publisher, those issues will be paywalled and only available to paying supporters.

More articles will be paywalled. I expect about half of the articles in 2026 will be paywalled as part of the book, and the other half will be free. Some paywalled articles may also be behind-the-scenes content about my work documenting and revitalizing languages, or deep-dives on special niche topics. The digest, however, will never be paywalled.

The price of paid subscriptions will increase to $10/mo. (USD). Since I’ll be publishing about twice as many articles this year (~50) and significantly more bonus articles (~25), I’ve decided to increase the price of a monthly subscription to $10/mo. (USD). Free subscriptions will remain free, and free subscribers will still have access to all my regular articles (~25/yr.). The new pricing model will go into effect on February 1, but if you’d like to lock in the old price of $5/mo. (USD) for another year, you can purchase an annual subscription for $50 now and avoid the price increase until 2027.

To recap, here’s the new pricing structure and benefits:

Free Subscribers ($0/mo.)

weekly digest

~25 free articles/year

Paying Subscribers ($10/mo. OR $100/yr.)

weekly digest

~25 free articles/year

~25 bonus articles/year

23rd International Linguistics Olympiad

The International Linguistics Olympiad (IOL) is an annual international competition that brings together secondary school students and experts from various fields of linguistics. Since its inception in 2003, the IOL has been hosted in a different country each year, traditionally between late July and mid-August. The competition challenges participants to analyze the grammar, structure, culture, and history of different languages and to demonstrate their linguistic abilities through puzzles and problem-solving challenges.

The IOL encourages creativity and imagination and helps participants develop skills in language analysis and problem-solving. By promoting awareness and understanding of diverse cultures and histories, the competition plays a vital role in nurturing future linguistics experts and contributing to the development of this academic field. No prior knowledge of linguistics or languages is required, as even the most challenging problems only require logical ability, patient work, and a willingness to think outside the box.

Why not give some of their past problems a try and see if you have what it takes to compete in the world’s toughest puzzles in language and linguistics?

This year’s IOL is being hosted in Bucharest, Romania in late July 2026. Learn more at the link below!

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week’s content from Linguistic Discovery.

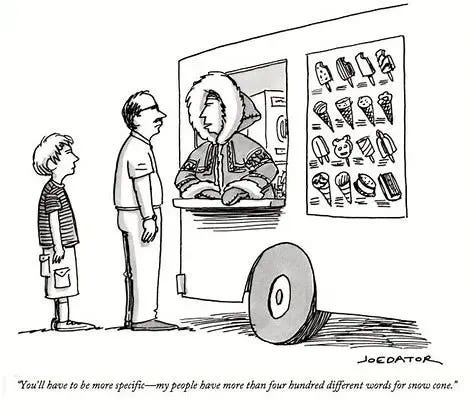

🆓 [no paywall] Do Inuit languages really have more words for snow?

Do Inuit languages really have hundreds of words for snow? ❄️ And if so, does it even matter?

A recent study uses data from 616 languages to claim that Inuit languages really do have disproportionately more words for snow than other languages.

In this issue of the newsletter (which is no longer paywalled), I explain the history of the “Inuit words for snow” myth, what this new study says about it, and whether language really does influence how we think:

How Spanish evolved from Latin

Another video from the archives this week: How Latin gradually evolved into Spanish (and various other Romance languages):

📰 In the News

Language and linguistics in the news.

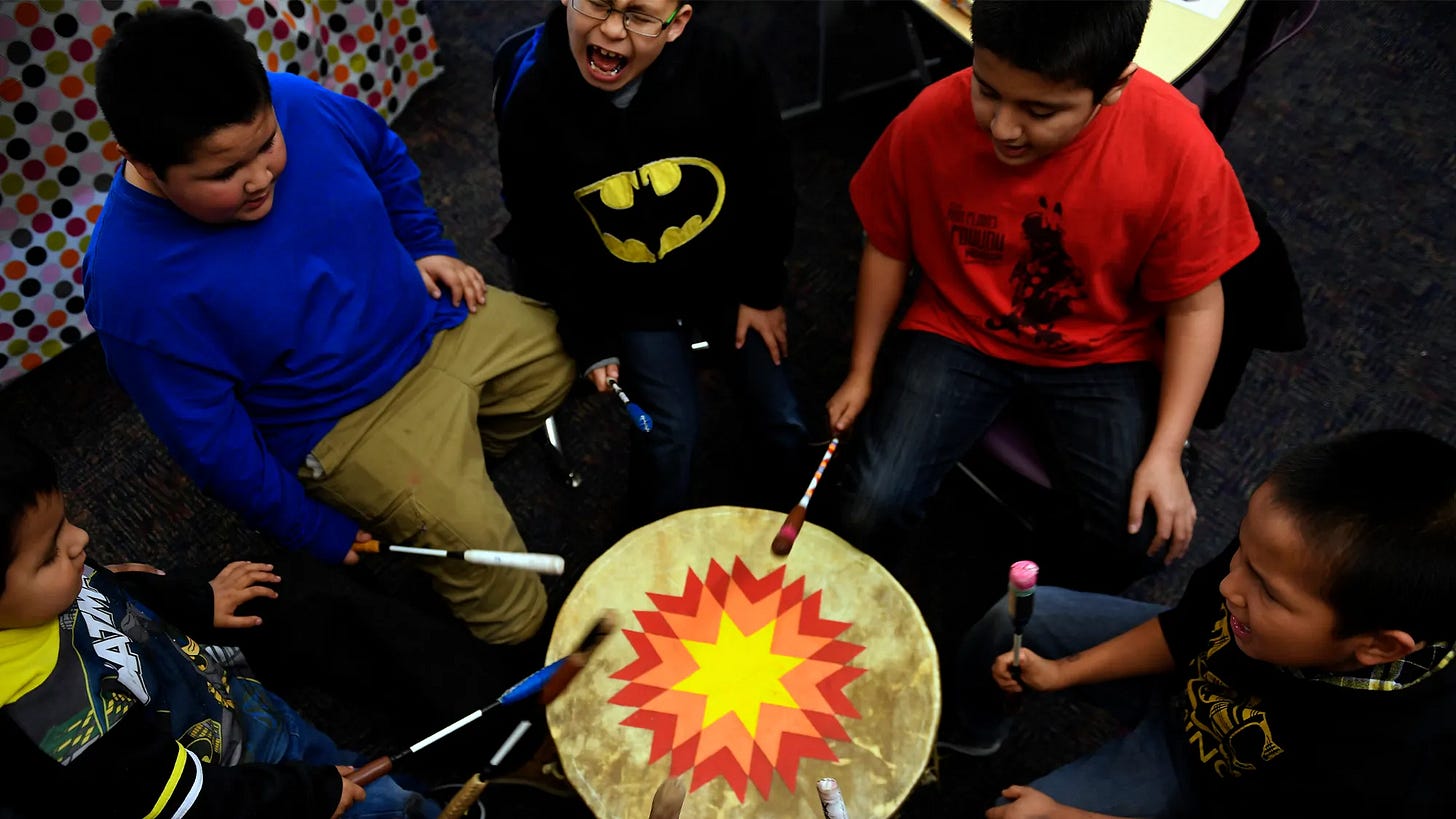

Linguists work to preserve Arapaho language with digital tools

Linguists have built databases of over 100,000 Arapaho sentences and 20,000 Arapaho words, representing data from almost 100 speakers, as part of an effort to document and revitalize the Arapaho language.

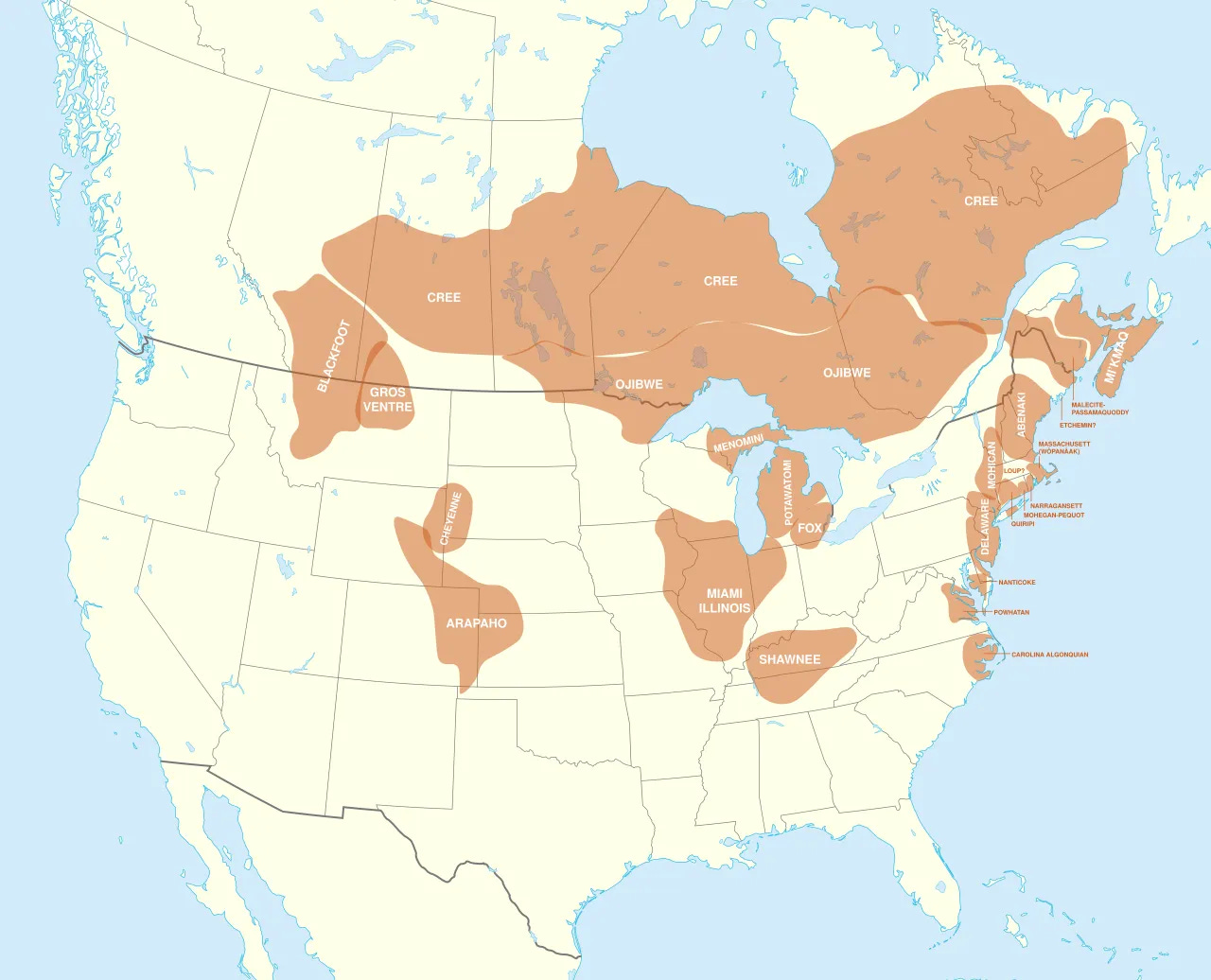

Arapaho is one of the many an Indigenous languages that are severely at risk of disappearing. According to the United Nations, 4 in 10 Indigenous languages are currently at risk due to aging populations and ongoing discrimination against native speakers. For Arapaho, the population of native speakers of the language rooted in the Great Plains is aging.

Arapaho is part of the extensive Algonquian language family, which spans much of northeast North America.

Digital linguists work to save the Arapaho language: New database built with over 100,000 Arapaho sentences (Popular Science)

A database could help revive the Arapaho language before its last speakers are gone (The Conversation)

First-ever monolingual Irish dictionary published

An Foclóir Nua Gaeilge is the first monolingual ‘Irish-Irish’ dictionary, allowing anyone searching for the meaning of an Irish word to do so without turning to English first. Until now, anyone wishing to look up a word in Irish had to rely on an Irish–English dictionary, meaning that a person seeking the meaning of a phrase as Gaeilge was first required to view it through the lens of English.

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

AI models can now analyze language as well as humans

A recent study put a number of large language models (LLMs) through a gamut of linguistic tests, similar to the types of problem sets given to undergraduate linguistics students.

“While most of the LLMs failed to parse linguistic rules in the way that humans are able to, one had impressive abilities that greatly exceeded expectations. It was able to analyze language in much the same way a graduate student in linguistics would—diagramming sentences, resolving multiple ambiguous meanings, and making use of complicated linguistic features such as recursion.”

In a first, AI models analyze language as well as a human expert (Quanta)

Beguš & Dąbkowski. 2025. Large linguistic models: Investigating LLMs’ metalinguistic abilities. IEEE Transactions on Artificial Intelligence. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1109/TAI.2025.3575745.

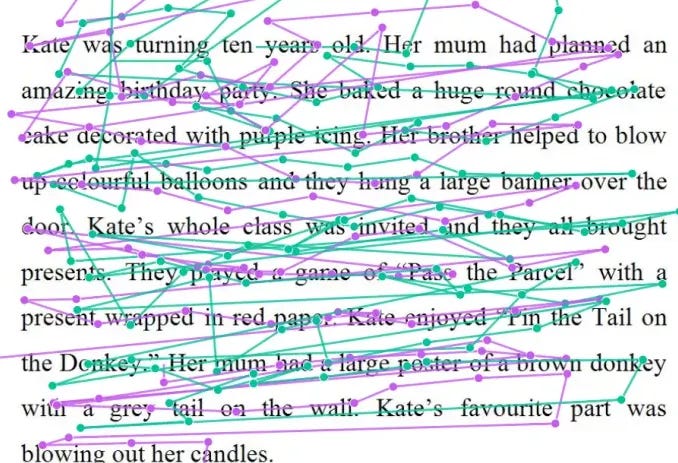

The way we read in our first language influences how we read in other languages

Languages are not all written in the same way. Some writing systems use letters (like English, Turkish), others use logographs (Chinese, Japanese), syllable characters (Hindi), and more. Some languages are read left to right (Russian, Spanish), and some right to left (Arabic, Hebrew).

Considering how diverse writing systems are, an interesting question is whether the way we read in our native language influences how we read in other languages. The answer appears to be yes, according to a recent study conducted using the Multilingual Eye-Movement Corpus (MECO). Approximately half of the variance in eye movement measures in the second language is explained by respective measures in the first language.

For example, writing systems like Korean pack a lot of information into smaller units, and eye-tracking data reflect this: Korean readers skip many words and have shorter eye movements, but make a lot more of them. In a language like Finnish, where words are much longer, information is more distributed and readers tend to spend more time on words and don’t skip them often. These are strategies that they carry over to their second language, even when the writing system is different.

New global research shows eye movements reveal how native languages shape reading (The Conversation)

Kuperman et al. 2025. Text reading in English as a second language: Evidence from the Multilingual Eye-Movements Corpus. Studies in Second Language Acquisition 45:1): 3–37. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263121000954.

📃 This Week’s Reads

Interesting articles I’ve come across this week.

Is a veggie burger still a burger? A linguist explains (The Conversation)

A database could help revive the Arapaho language before its last speakers are gone (The Conversation)

In contrast to the study above about LLMs doing metalinguistics.

My two cents: Languages don’t need “tidying up”!

What’s the least spoken language in the world? (Duolingo)

A look at a few highly endangered languages: Taushiro (Peru), Kusunda (Nepal), Njerep (Cameroon), Ket (Siberia), and Tanema (Solomon Islands).

📚 Books & Media

New (and old) books and media touching on language and linguistics.

Immigrant tongues: Exploring how languages moved, evolved, and defined us

This book was released in August 2025 but only just came across my radar, and personally I’m pretty excited to read it. It looks similar in some ways to one of my all-time favorite books, Empires of the word: A language history of the world by Nicholas Ostler (Amazon | Bookshop.org). Here’s the publisher’s blurb:

Patrick Foote’s Immigrant Tongues is the ultimate language history book, blending stories of migration, culture, and evolution to uncover how languages have shaped our world. Perfect for fans of linguistics gifts and etymology dictionaries, this book combines the fascinating history of English language development with tales of other lingua francas and their profound global impact.

From the history of the English language’s arrival in the United States to the spread of Arabic across North Africa and the enduring legacy of the Latin language, Immigrant Tongues explores the journeys of tongues across continents. Each chapter delves into the origins of a language, the native tongues it encountered, and how it adapted and evolved in its new home. With a style that balances entertainment and depth, this linguistics book also highlights the cultural exchanges that enriched language along the way.

Grab a copy here:

The origin of language: How we learned to speak and why

Here’s a review of the book from New Scientist:

Did childcare fuel language? A new book makes the case (New Scientist)

Grab a copy here:

👋🏼 Til next week!

Apropos my article about Inuit words for snow:

The Amazon and Bookshop.org links on this page are affiliate links, which means that I earn a small commission from Amazon for purchases made through them (at no extra cost to you).

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!