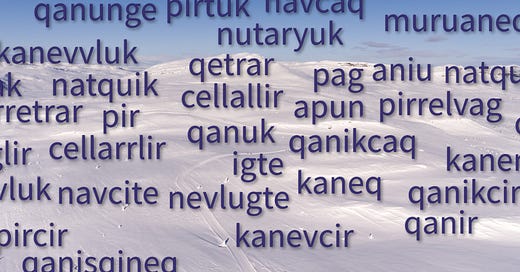

Do Inuit languages really have more words for snow? And why does it matter, anyway?

A new study shows that Inuit languages really do have more words for snow, but what does that tell us about language?

One of the most infamous language tropes is the idea that Inuit languages have dozens or even hundreds of words for snow—more than any other languages. Now, this idea may or may not be true (more on that in a bit), but it’s instructive to understand where this trope came from in the first place. Here it is, from Franz Boas in the Handbook of American Indian languages (1911):

Another example of the same kind, the words for SNOW in Eskimo1, may be given. Here we find one word, aput, expressing SNOW ON THE GROUND; another one, qana, FALLING SNOW; a third one*, sirpoq*, DRIFTING SNOW; and a fourth one, qimuqsuq, A SNOWDRIFT. (Boas 1911: 25–26)

That’s it. That’s the entire basis for the claim that Inuit languages have an exorbitant number of words for snow.

This idea was repeated and exaggerated in greater and greater numbers over the decades, until by 1984 the New York Times reproduced the number as 1002:

Benjamin Lee Whorf, the linguist, once reported on a tribe that distinguishes 100 types of snow – and has 100 synonyms (like tipsiq and tuva) to match. (“There’s snow synonym,” New York Times)

Why are people so obsessed with the “Inuit words for snow” myth? It has everything to do with the idea that language fundamentally affects the way we think. But is this idea true?

Does language influence the way we think?

Where things start to get really interesting is in the nuanced interplay between language and experience. Our conceptualizations and experiences shape our language, but our language also has subtle effects on our conceptualizations, creating a feedback loop.

The “Inuit words for snow” myth captures the popular imagination because it creates an exoticized image of peoples who “see the world differently” or “think differently” than English speakers. This is a version of an idea known as linguistic relativity (also called the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis)—the idea that the language a person speaks influences, limits, or determines the way that they perceive and conceptualize their worlds (Matthews 2014: 353; Crystal & Yu 2024: 398).

In one understanding of the idea, linguistic relativity is trivially true. All our experiences influence the way we think in extremely subtle ways, language included. This is no different than saying that the sport a person plays or the job a person does or how much exercise a person gets influences how they think about things. That’s all true, but also pretty unremarkable.

A more extreme version of the idea, called linguistic determinism, claims that we are locked into certain worldviews by the languages we speak. This claim is obviously false. The fact that people can successfully learn other languages is enough evidence that linguistic determinism cannot be literally true. Or consider this simple thought experiment: The Russian language has distinct words for ‘light blue’ (голубой goluboj) and ‘dark blue’ (синий sinij), yet English has just one word for both, blue. Are English speakers incapable of understanding the difference and distinguishing between the two colors because English lacks distinct words for them? Of course not. Languages are also not fixed entities—speakers of any language rapidly coin new expressions for ideas and things that are new to them.

Unfortunately, linguistic determinism has a sordid history of being used to justify all sorts of scurrilous claims about the inferiority of indigenous peoples, by both scholars and the public alike. For example, in a grammatical description of Inuit languages, philologist William Thalbitzer writes:

In the Eskimo mind the line of demarcation between the noun and the verb seems to be extremely vague, as appears from the whole structure of the language, and from the fact that the inflectional endings are, partially at any rate, the same for both nouns and verbs. […] Judging from these considerations, we get the impression that to the Eskimo mind the nominal concept of the phenomena of life is predominant. The verbal idea has not emancipated itself from the idea of things that may be owned, or which are substantial. Anything that can be named and described in words, all real things, actions, ideas, resting or moving, personal or impersonal, are subject to one and the same kind of observation and expression. […] The Eskimo verb merely forms a sub-class of nouns. (Thalbitzer 1911: 1057–1059)

Here we see a scholar using the purported lack of a grammatical distinction in the language to say that Inuit peoples are incapable of distinguishing objects from actions. In this view, their categorization of the world is hopelessly vague.

In another case the opposite was claimed: linguist Stephen Ullmann criticized some indigenous languages for being too specific instead:

To have a separate word for all the things we may talk about would impose a crippling burden on our memory. We should be worse off than the savage who has special terms for wash oneself, wash someone else, but none for the simple act of washing. (Ullmann 1951: 49).

Ullmann is unwittingly referring to Cherokee, which has its own version of the “Inuit words for snow” myth. In 1892, linguist Otto Jespersen described Cherokee as having 13 different verbs for washing, a claim which holds up to scrutiny just about as well as the “Inuit words for snow” myth (Hill 1952), as we’ll see below. But like the snow myth, that idea was propagated for decades afterwards by various scholars, with the result that a generation of intellectuals thought that the Cherokee were incapable of abstract thought.

The most famous claim about “the indigenous mind” comes from the progenitor of linguistic determinism himself, Benjamin Lee Whorf:

After long and careful study and analysis, the Hopi language is seen to contain no words, grammatical forms, constructions, or expressions that refer directly to what we call “time”. [A Hopi person] has no general notion or intuition of TIME as a smooth flowing continuum in which everything in the universe proceeds at an equal rate. (Whorf 1950: 67)

Yet in 1983, linguist Ekkehart Malotki published a hefty 677-page tome analyzing all the expressions for time in the Hopi language. The book opens with the following passage in Hopi, with accompanying translation:

pu’ antsa pay qavongvaqw pay su’its talavay kuyvansat, pàasatham pu’ pam piw maanat taatayna

‘Then indeed, the following day, quite early in the morning at the hour when people pray to the sun, around that time then, he woke up the girl again.’ (Malotki 1983)

Oops. Suffice it to say, Whorf’s analysis was slightly off.

These kinds of linguistically-motivated claims about the cognitive abilities of different peoples extend to more than just indigenous communities. It’s been claimed that because some languages lack dedicated morphological markers of future tense, speakers of those languages save less money and are generally worse at long-term, future-oriented decision-making than speakers of languages which do have a future tense (Chen 2013).

What’s especially ironic about this study is that most linguistic typologists (myself included) would include English in the group of languages lacking a dedicated future tense.3 But this study does the opposite, contrasting English with Mandarin Chinese, for example. The paper concludes that speakers of non-tensed languages like Mandarin “save more, retire with more wealth, smoke less, practice safer sex, and are less obese”—huge if true. In fact, the author Keith Chen even gave a TED talk about his research, garnering over 250,000 views on YouTube:

Yet it turns out the study was deeply flawed: It did not take into account the fact that many languages in the study were related; it assumed that each language was independent. This assumption makes correlations appear stronger than are warranted (known as Galton’s problem in phylogenetics). In a follow-up study that controlled for relatedness and included Chen as a coauthor, the statistical correlation between tensedness and future-orientation was found to be insignificant, debunking Chen’s original study (Roberts, Winters & Chen 2015).

In addition to the pernicious beliefs propagated by uncritical acceptance of linguistic relativity, claims about linguistic relativity usually have the direction of causation wrong as well. It’s not that language shackles us into certain ways of seeing the world; it’s that language comes to reflect our conceptualizations of the world. Languages develop vocabulary and grammatical structures for things that speakers talk about frequently—a pretty trivial observation. Geoffrey Pullum trenchantly makes this point in his famous essay, “The great Eskimo vocabulary hoax”:

Among the many depressing things about this credulous transmission and elaboration of a false claim is that even if there were a large number of roots for different snow types in some Arctic language, this would not, objectively, be intellectually interesting; it would be a most mundane and unremarkable fact.

Horsebreeders have various names for breeds, sizes, and ages of horses; botanists have names for leaf shapes; interior decorators have names for shades of mauve; printers have many different names for different fonts (Caslon, Garamond, Helvetica, Times Roman, and so on), naturally enough. If these obvious truths of specialization are supposed to be interesting facts about language, thought, and culture, then I’m sorry, but include me out. (Pullum 1989: 278–279)

(Pullum’s article is available here, but the book version has an added appendix where Pullum attempts to get at a real number.)

Where things start to get really interesting is in the nuanced interplay between language and experience. Our conceptualizations and experiences shape our language, but our language also has subtle effects on our conceptualizations, creating a feedback loop. For instance, while it’s true that English speakers can distinguish light blue and dark blue, it turns out they can’t do it as well or fast as Russian speakers can:

Russian speakers get the blues (New Scientist)

Winawer et al. 2007. Russian blues reveal effects of language on color discrimination. PNAS 104(19): 7780–7785. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0701644104

Lera Boroditsky, one of the authors of the above paper, has an excellent TED talk (in the top 30 of TED’s most-viewed talks) describing some of the great research that’s been done in this area:

Do Inuit languages really have more words for snow?

Okay, so the original discussion got blown way out of proportion, sure, but could the claim that Inuit languages have lots of words for snow still be true, even if it doesn’t tell us anything scientifically interesting? After all, it’s entirely reasonable that a community would have an assortment of words for objects they deal with frequently.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Linguistic Discovery to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.