How hypothetical are protolanguages?

How hypothetical are protolanguages? How did the Indo-Europeans spread? What does conversation look like in the brain? Here’s what happened this week in language and linguistics.

Welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Dispatch, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics.

This week we’ll talk more about the spread of the Indo-European peoples, new techniques for mapping conversation onto specific neural patterns, and just how hypothetical protolanguages really are. 🤔

This week’s issue of Discovery Dispatch is sponsored by The Humane Space, an app that injects more curiosity into your daily life through beautiful immersive lessons and guided contemplations.

I had the great pleasure of getting to work with The Humane Space last year to put together a week’s worth of lessons on linguistics (which you can see here!), and I love the philosophy with which they approach their lessons. They aim to inject a little wonder and curiosity into your every day, which is exactly what I try to do with Linguistic Discovery. Their lessons cover a huge range of topics, from linguistics to weaving to gardening to the Norse goddess of winter Skaði. Every day is a little intellectual adventure.

If you’re interested in trying out The Humane Space, you can get a free month subscription to the app at the link:

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week's content from Linguistic Discovery.

Linguistic Idiocentrism

Whenever I mention any sort of dialect diversity in English (words, phrases, or pronunciations that are particular to specific dialects) on social media, I inevitably receive comments along the lines of “nobody says that” or “that’s incorrect”, rather than simply, “I’ve never encountered that. That’s different from how I talk.” Seeing this so often on social media reminds me of the False Consensus Fallacy:

a pervasive cognitive bias that causes people to “see their own behavioral choices and judgments as relatively common and appropriate to existing circumstances”. (Wikipedia: False consensus effect)

You might call the linguistic version of this Idiolectal Bias or maybe Linguistic Idiocentrism—the belief that your particular way of speaking is in some way more common, standard, or correct. This is why most people think they don’t speak with an accent. The reality is, however, we don’t have as much exposure to other ways of speaking as we think; and even when we do encounter such variation, we’re really bad at noticing it. I linked to a study a few weeks ago that showed just how bad, in fact:

So the next time you encounter a way of speaking you’ve never heard before, consider the strong likelihood that a lot more people say it that way than you realize!

How hypothetical are protolanguages?

Last year I partnered with the language learning company Rosetta Stone to make a series of educational videos about linguistics, one of which explains (briefly, and at a very high level) what protolanguages are and how linguists reconstruct them.

The Rosetta Stone blog has now expanded upon that in their latest article:

The article states that some common characteristics of protolanguages include:

limited linguistic complexity

limited vocabulary

no known pronunciation

The article also states, “Since protolanguages are prehistoric and hypothetical, you won’t find much evidence of them except as linguistic theories”

I want to criticize this just a bit, or at least add some nuance:

First, there aren’t any protolanguages that have no known pronunciation. The whole process of reconstructing protolanguages involves determining what its original sounds were. If we didn’t have enough data to do that, we couldn’t reconstruct a protolanguage at all. Figuring out the historical pronunciations is what makes a protolanguage.

That said, there can be a great deal of uncertainty about how specific sounds in a protolanguage are pronounced. For example, we know that Proto-Indo-European had a set of consonants traditionally called “laryngeals”, but we’re not entirely certain of what their exact pronunciation was.

Second, while it’s true that there’s no written evidence of protolanguages, there’s ample linguistic evidence for them in their modern descendants. Linguists have been developing techniques for deducing words and features of protolanguages based on their descendants for nearly 250 years now, and we’ve gotten pretty good at it. We’ve even been able to confirm those results in some cases, such as when new inscriptions of ancient languages have been uncovered. The discovery of Hittite tablets, for example, helped confirm Saussure’s theory that Proto-Indo-European had laryngeal consonants. As another example, we can also use modern Romance languages to reconstruct Latin, and compare that to written versions of Latin from the same time period. This shows us that the techniques work and provide a decent approximation of what the actual language was like.

Of course, as with any new scientific technique that sparks excitement about the additional mysteries it may help unlock, many scholars have eagerly overapplied these techniques in ways that are inappropriate (which is why there are still so many wildly speculative theories about superfamilies like Altaic or Amerind). Historical reconstruction has its limits. No historical linguist thinks that the protolanguages they reconstruct are a completely accurate representation of how the language was actually spoken (I hope). Languages are riddled with exceptions, for starters, and if one of those exceptions was later regularized it’s likely we’d never know about it. Similarly, if all the child languages of a protolanguage happen to lose the same feature—say, they all lose the sound /k/, or they all borrow a new word for ‘sun’—then it’s unlikely we’d ever know about that feature. We’d be forced to conclude based on the available evidence that the protolanguage didn’t have a /k/ sound or a word for ‘sun’—even though we know this is incredibly unlikely. Languages without /k/ are exceedingly rare, and I don’t know of any language without a word for ‘sun’. Sometimes the lost features leave behind subtle traces of their existence in other ways (such as how Ferdinand de Saussure was able to infer the existence of laryngeal consonants in Proto-Indo-European based on their subtle effects on surrounding sounds before they were lost), but obviously this kind of evidence is difficult to find.

These limitations are why protolanguages appear to have limited linguistic complexity and limited vocabularies, but we know that’s not actually what those protolanguages were like. All human languages are linguistically complex and have robust vocabularies. So when we reconstruct protolanguages with vocabularies of only 500 words, or ones that lack the ability to express future actions, there’s an implied asterisk saying, “We know this isn’t 100% correct, but it’s the only reconstruction we have evidence for, and we would be abandoning scientific principles if we tried to reconstruct aspects of the language without sufficient evidence.” The amount of evidence for any given word or feature varies, of course, but linguists use inference to the best explanation to decide the best reconstructions given the evidence they have.

Protolanguages are hypothetical in the same way that the Higgs boson was hypothetical until 2012. Only some of their properties are known, and those hypothetical properties are based on the best available scientific evidence and understandings of how language works. Additional evidence may yet prove them partially or completely accurate or inaccurate. While protolanguages may be hypothetical, that doesn’t make them unscientific.

Pedantic quibbling aside, Rosetta Stone’s blog post is a fun one, and the author makes a great analogy to genetics that’s helpful in understanding historical reconstruction too. Have a read here:

📰 In the News

Language and linguistics in the news.

In response to Trump’s executive order declaring English the official language of the executive branch, the Linguistic Society of America (LSA) has issued a statement against it:

The LSA’s main points, backed by various studies which they cite, are:

The United States has always been a multilingual country, and this gives it strength.

Citizens of the US and of all democracies inevitably have different linguistic ways of navigating their lives, and enforced monolingualism never achieves national unity.

“Official English” policies do not improve economic prospects for those who arrive in the US speaking another language, nor do they improve communication for those who live in multilingual communities.

Supporting and promoting multilingualism makes a nation stronger, not weaker.

In a similar but more caustic vein, linguists Mark Turn and Ross Perlin (the latter of whom authored the bestselling book Language city: The fight to preserve endangered mother tongues in New York [Amazon | Bookshop]) wrote an article in The Conversation trenchantly attacking Trump’s order as reflecting the president’s own “linguistic insecurity, […] weakness, and fear”.

Trump’s English language order upends America’s long multilingual history (The Conversation)

For my own take on Trump’s order, check out this issue of the newsletter:

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

Predicting what conversation looks like in the brain

Researchers have long tried to map different aspects of speech onto activity in different regions of the brain. As you might expect, it’s nowhere near as straightforward as we’d like: saying the word “apple” doesn’t always light up the same areas of the brain in the same ways. Language is highly context-dependent. And speech is such a complex network of sounds and words and syntactic constructions and meanings that it’s impossible to cleanly map these various components of language onto brain activity. In the past, researchers have avoided this problem by focusing on just one aspect of speech at a time—prosody (like we looked at the other week), syntax, meaning, etc.

Babies can learn multiple languages from birth—and they’ll slow the onset of dementia if they do

There was all sorts of interesting research in linguistics this week! Let’s dive in!

This study uses a speech recognition model called Whisper instead, which is designed to transcribe audio recordings of natural conversations. Whisper analyzes the speech stream at multiple levels, just like language itself—low-level acoustic information all the way up to high-level information about which words tend to appear in which contexts. The authors recorded about 100 hours of conversation while monitoring the brain activity of the speech participants using electrocorticography (ECoG)—a corpus of 520,209 words, which is incredibly large for an experiment measuring brain activity. Traditional experiments in this area involve participants reading a passage of text or just a few dozen sentences. So the scale of the data for this study is remarkable, enabling a much more accurate computational model of speech.

What the authors found is that the internal representations created by the Whisper language model mapped onto brain activity better than traditional computational models which don’t create these hierarchical internal representations. And they were able to watch speech production and processing happen in real-time. They could see, for example, that the brain progresses from thinking about what it wants to say, to beginning to form sounds. Then, after listening, the brain thinks back on what was just said.

Reporting: Smooth talker: Hebrew University study gives insight into brain’s role in linguistic interaction (The Jerusalem Post)

Original Research Article: A unified acoustic-to-speech-to-language embedding space captures the neural basis of natural language processing in everyday conversations (Nature Human Behavior)

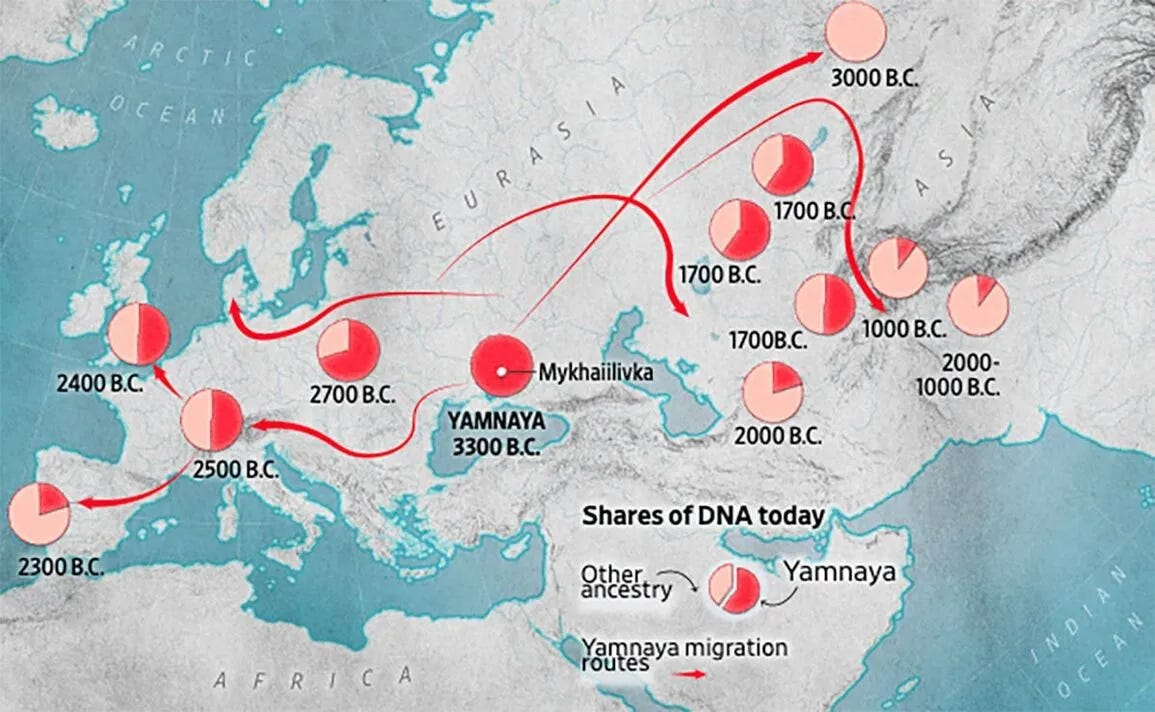

The genetic spread of the Indo-Europeans

I reported last month that new DNA evidence helped further solidify our understanding of the origins of the Indo-European peoples and their language, called Proto-Indo-European. Current evidence tells a story where Pre-Indo-European peoples migrated from Anatolia to the Ukrainian steppe just north of the Black Sea sometime before 3000 BCE. They then mixed with the local people there, becoming a group that archaeologists call the Yamnaya.

The quest for the first Indo-Europeans, and whales communicating like humans

It’s an exciting week in the world of linguistics! Two studies were just published that are each creating quite the media buzz—I give you the tl;dr below!

The Yamnaya would go on to have a profound impact on Eurasian history. They were likely the first people to ride horses and use wheeled carts, making them an unstoppable invading force for other cultures of Eurasia at the time. They spread rapidly across the Eurasian steppe and throughout Europe, bringing their languages with them and often killing the males of any society who resisted. As a result of this tidal wave of cultural replacement and the subsequent histories of their descendants, today about 42% of the world’s population speaks an Indo-European language.

While last month’s reporting on this research focused on its linguistic implications, this round of reporting is now drawing attention to the genetic implications: the descendants of the original Indo-Europeans can trace their ancestry to the Yamnaya of 5,000 years ago—and indeed to a single hamlet in the Russian-occupied region of Ukraine called Mykhailivka, an archaeological site spanning 3635–3383 BCE. The authors came to this conclusion by analyzing the DNA samples from 450 prehistoric individuals taken from 100 sites in Europe, as well as data from 1,000 samples that had been previously analyzed. The DNA of an individual from Mykhailivka is the crucial genetic link between the earlier peoples that migrated into the region and the later Yamnaya.

Reporting: The ancient horsemen who created the modern world (WSJ)

Non-paywalled version available at MSN here.

Original Research: A genomic history of the North Pontic Region from the Neolithic to the Bronze Age (Nature)

That’s it for this week! Thank you so much for being a subscriber, and I hope you enjoyed this issue! If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery and help educate the world about the science and diversity of language, consider becoming a supporter! You’ll get the occasional bonus article/video and early access to chapters of my book!

Have a great week!

~ Danny

🚫 Errata

Corrections and clarifications.

In my post on guacamole, I said that the word mōlli meant ‘sauce’, and while this is true, it obscures the fact that mōlli, like āhuacatl ‘avocado’, has a noun suffix at the end of it. The -tl suffix becomes -li after stems ending in /l/, so the base of mōlli is just mōl-.

I also had a small typo in the word āhuaca-.

Taking all this into consideration, I updated the etymological flowchart for ‘guacamole’, and the text of the accompanying article:

guacamole = avocado mole

When the Spanish began their conquest of Mesoamerica in 1519, the dominant language in the region near modern-day Mexico City was Aztec—or as it’s called in the language itself, Nahuatl (pronounced in English as /ˈnɑ.wɑ.təl/ and in the language itself as /ˈnaː.wat͡ɬ/). The

The Amazon and Bookshop.org links on this site are affiliate links, which means that I earn a small commission from those companies for purchases made through them (at no extra cost to you).

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!