Bonobos combine their vocalizations the way humans combine words—a trait once thought unique to humans

Bonobos challenge the uniqueness of human language, penguins learn etymology, and China adopts a new gender-neutral pronoun. Here’s what happened this week in language and linguistics.

Did you know that if you want to say something without someone nearby being able to understand, you can just say it in the International Phonetic Alphabet?

Welcome to this week’s edition of Discovery Dispatch, a weekly roundup of the latest language-related news, research in linguistics, interesting reads from the week, and newest books and other media dealing with language and linguistics.

This week’s issue of Discovery Dispatch is sponsored by The Humane Space, an app that injects more curiosity into your daily life through beautiful immersive lessons and guided contemplations.

I had the great pleasure of getting to work with The Humane Space last year to put together a week’s worth of lessons on linguistics (which you can see here!), and I love the philosophy with which they approach their lessons. They inject a little wonder and curiosity into your every day, which is exactly what I try to do with Linguistic Discovery. Their lessons cover a huge range of topics, from linguistics to weaving to gardening to the Norse goddess of winter Skaði. Every day is a little intellectual adventure.

If you’re interested in trying out The Humane Space, you can get a free month subscription here:

📢 Updates

Announcements and what’s new with me and Linguistic Discovery.

LingComm25

This week I attended the third biannual Linguistics Communication conference (LingComm25), which focuses on supporting and bringing together people who are communicating linguistics to broader audiences—whether that be through newsletters like this one, social media, news interviews, podcasts, museum exhibits, school programs, or anything else. It was a ton of fun, and I got to meet lots of other ling communicators I hadn’t connected with before, including:

Heddwen Newton (author of the English in Progress newsletter)

Charlotte Vaughn (Founder/Director of the Language Science Station at Planet Word)

Adam Aleksic (@etymologynerd on social media)

Daniel Midgley (Because Language podcast)

Ingrid Piller (Language on the Move)

Jana Viscardi (@JanaViscardi on YouTube)

And of course I got to connect with some old friends as well!

Dan Mirea (@danniesbrain on social media)

Gretchen McCulloch (Lingthusiasm, Because Internet)

Colette Feehan (@CMFVoices on social media)

I was a panelist for a session on using social media for lingcomm, and participated in a community-led session on newsletters as well, and I was very happy with how both sessions went. I even had a few people tell me they came away from those sessions encouraged and excited to create more lingcomm content!

Overall it was a fantastic event, and I came away inspired to continue making this newsletter and my social media content even better.

If you’re thinking about getting into linguistics communication or are already doing lingcomm and want ideas for how to do it even better, I highly recommend attending the next conference in 2027. And if you’d like to present a talk/poster or be a panelist, I’ll be on the organizing committee for LingComm27, so let me know!

guacamole everywhere

Something that happens more often than you’d think among us linguistics communicators is that we’ll cover the same topic, sometimes in extremely similar ways!

For example, myself, Adam Aleksic (@etymologynerd), and Griffin Basset (TikTok: @wordsatwork | Instagram: @w0rdsatw0rk) have all made videos about “dummy” pronouns (also called pleonastic or expletive pronouns).

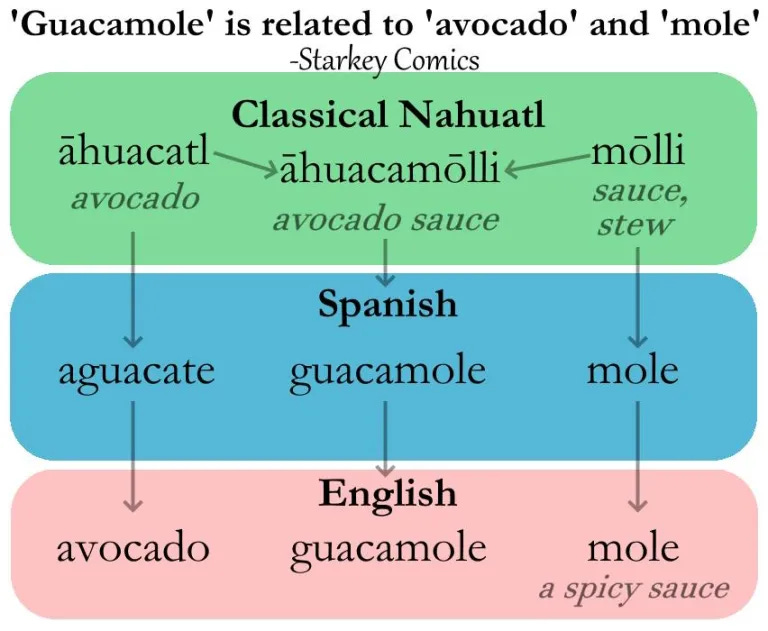

More recently, I and two other creators who do etymology posts have looked at the history of the word guacamole:

Linguistic Discovery

guacamole = avocado mole

When the Spanish began their conquest of Mesoamerica in 1519, the dominant language in the region near modern-day Mexico City was Aztec—or as it’s called in the language itself, Nahuatl (pronounced in English as /ˈnɑ.wɑ.təl/ and in the language itself as /ˈnaː.wat͡ɬ/). The

Starkey Comics

Yoïn van Spijk

Even Babbel the language learning app hopped on the guacamole trend! (Though they got the facts wrong!)

I was actually so surprised at how similar Ryan Starkey’s infographic is to mine that at first I requested that Facebook take it down for copyright infringement. But Ryan kindly reached out to me and explained that it really was a total coincidence, so I apologized and retracted the takedown request. To be quite honest, I should have given Ryan the benefit of the doubt, because he’s been producing excellent, original, high-quality infographics like this for years. But we had a productive email conversation about it and we’re both looking forward to supporting each others’ work going forward.

In any case, all this is a great reminder that us lingcommers aren’t really in competition with each other. If you write about etymology, chances are at some point you’ll write about guacamole, because it’s a fun/interesting story. Plus there are only so many ways you can structure an etymological diagram. The results are bound to come out similar. But each of us has their own style, perspective, and focus, which just makes for a richer and more interesting experience for all of our followers.

So if you haven’t looked at either Ryan Starkey’s or Yoïn van Spijk’s work yet, be sure to take a look here:

🆕 New from Linguistic Discovery

This week's content from Linguistic Discovery.

penguin etymology

Last week the penguins of Heard Island and McDonald Islands, Australian territories near Antarctica, were slapped with 10% tariffs by Trump. The internet is reeling with the injustice of it all, and I’ve been summoned to bring all my linguistics skills to bear in aiding the hapless penguins:

So here’s the complete etymological flowchart for penguin:

You can read all the details at this latest issue of the newsletter:

The etymology of “penguin”

The penguins of Heard Island and McDonald Islands, Australian territories near Antarctica, have been slapped with 10% tariffs by Trump. The internet is reeling with the injustice of it all, and I’ve been summoned to bring all my linguistics skills to bear in aiding the hapless penguins:

📰 In the News

Language and linguistics in the news.

Amid anxiety about the future of French, a Quebecker’s guide to slang welcomes immigration’s influence (The Globe & Mail)

Tibet is one of the most linguistically diverse places in the world. This is in danger of extinction. (The Conversation)

Chinese only introduced a feminine pronoun in the 1920s. Now, it might adopt a gender-inclusive one. (The Conversation)

Louisiana has a long history with French. This immersion school aims to keep it alive. (NPR)

Most lessons in English to be phased out in Welsh county (BBC)

🗞️ Current Linguistics

Recently published research in linguistics.

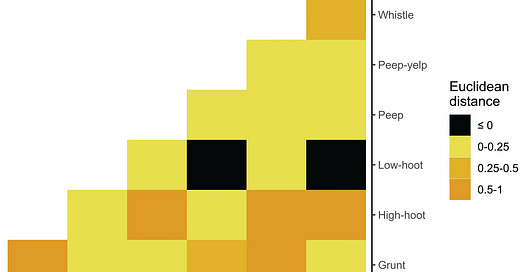

Bonobos combine vocalizations similarly to how humans combine words

Bonobos like Kanzi continue to surprise us with their linguistic abilities. A new study published last week by researchers at the University of Zürich and Harvard University provides evidence that bonobos combine their vocalizations in a way similar to how humans combine their words into phrases—a property called compositionality.

There are two types of compositionality: trivial and nontrivial. In trivial compositionality, combining two words results in a meaning that is just the sum of its parts. “tall dancer” refers to someone who is both tall and a dancer. In nontrivial compositionality, one of the words modifies the other: “bad dancer” does not refer to a bad person, just a person who doesn’t dance well. “bad” is interpreted in the context of “dancer” alone.

This study claims that bonobo vocalizations exhibit both types of compositionality. For example, bonobos have a peep that means ‘I would like to …’ and a whistle which means ‘let’s stay together’, and when combined they get used in tense social situations to mean ‘let’s relax’. Other vocalizations are the yelp, meaning ‘let’s do that’, and the grunt, meaning ‘look at me’, but when used together they seem to invite others to build a night nest.

This is an exciting claim, because compositionality has long been considered a design feature of language that’s unique to humans. I wrote about the design features of language a bit in my post on Three-Body Problem, where I discuss what alien languages could teach us about human language:

If the claim of this study holds up to scrutiny, it would dismantle yet another property of language once thought to be unique to humans. As I wrote in my article on Kanzi:

At the extreme, many linguists argue that there are no cognitive abilities that are unique to language. Humans are simply the only species to have developed all of these abilities together, and to a sufficient degree. This approach to language is called functionalism or cognitive linguistics.

This study would seem to provide further evidence in support of this functionalist view. You can read more about the implications of this perspective in my article about Kanzi:

Kanzi (1980–2025)

In the early 1980s, a team of researchers led by Sue Savage-Rumbaugh at Emory University’s Yerkes Regional Primate Research Center were struggling to teach a bonobo named Matata how to use a symbolic picture system called Yerkish to communicate. Each symbol, called a

Naturally, being such a bold claim, this research has garnered a great deal of attention from the media too:

Press Coverage

Bonobos create phrases in similar ways to humans, new study suggests (The Conversation)

There might be something human in the way bonobos communicate—their calls share a key trait with our language, study suggests (Smithsonian Magazine)

Bonobos’ complex calls share an extraordinary trait with human language (Scientific American)

‘Uniquely human’ language capacity found in bonobos (Science)

Peeps and yelps show bonobos communicate with added meaning, study says (Washington Post)

Bonobos use a kind of syntax once thought to be unique to humans (New Scientist)

Original Research Article

Berthet, Surbeck, & Townsend. 2025. Extensive compositionality in the vocal system of bonobos. Science 388(6742): 104–108. DOI: 10.1126/science.adv1170

Further Reading

Other New Research

I reported the other week about a neat study mapping a speech recognition model to neural patterns in the brain, and here’s some additional reporting on that:

AI analysis of 100 hours of real conversations — and the brain activity underpinning them — reveals how humans understand language (Live Science)

Other new and interesting research:

Are Scottish accents really more aggressive? A linguist explains. (The Conversation)

Why you should think twice before using shorthand like “thx” and “k” in your texts (The Conversation)

Esperanto and Klingon perceived as equally familiar as English and Mandarin (Science Magazine)

📃 This Week’s Reads

Interesting articles I've come across this week.

Kanzi’s death seems to have spurred more interest in animal communication recently, and as a result we have a couple articles about the topic this week:

Can animals understand human language? (Live Science)

The animals revealing why human culture isn't as special as we thought (New Scientist)

NativLang on YouTube also has an ongoing series about the topic. He recently released another entry in the series as well:

Other reads from the week:

Accent vs. Dialect vs. Language: What’s the difference? (Mental Floss)

Why is it so hard to type in indigenous languages? (The Conversation)

What we can learn from U.S. place names (Duolingo)

The lore of “lore”—How fandoms created an online phenomenon from an Old English word (The Conversation)

📚 Books & Media

New (and old) books and media touching on language and linguistics.

The sixth edition of Understanding syntax, an introductory syntax textbook, came out last month and I snagged a copy of it. What I’ve always appreciated about this book is its typological focus, with tons of examples from a wide range of languages. This is a welcome breath of fresh air compared to most syntax textbooks, which focus heavily or sometimes even exclusively on English—a trend I find rather unsavory. Understanding syntax also takes a broad conception of syntax, and includes discussions of parts of speech, grammatical relations, and transitivity, rather than the narrow focus on constituency that preoccupies most books on the topic. So if this is an area you’d like to learn more about, grab a copy here:

Content creator Landon Bryant (@LandonTalks on Instagram and TikTok), who talks all about Southern language and culture, just released his first book, Bless Your Heart: A field guide to all things Southern. I’ve only just started it, but it’s a fun, endearing, wonderful book so far:

And since this is the end of this week’s digest, I’ll leave you with a little excerpt from the book about the “Southern Goodbye”:

Something that you’ll experience in the South—and that you will eventually participate in—is the Southern goodbye. I believe people in the Midwest call it a Midwestern goodbye, and what it means is—we’re not leaving, or at least we’re not leaving yet. It means get comfortable. It doesn’t mean we’re about to go. First it starts with a,

“Well…” and that’s the first indication, but you still have a couple of hours. An hour or two later, somebody might even stand up and maybe walk to the edge of the room, but then they’ll cross their arms and lean up against the molding for a little bit. Then they’ll have some more conversations. Then maybe they might make it into the kitchen, and here, at this point, they should be starting to be aware that they are actually gonna leave, but they don’t need to put any stock into it yet—they haven’t even made it to the driveway.

Once they’ve made it through their kitchen conversation or whatever the room is that’s adjacent to the front door, they’ve gotta head to the driveway. Now, the driveway combo is one where they are fully pretending they’re leaving. If you were not familiar with a Southern goodbye, you would think they’re almost out of there, but they’re not.

If you’re a little kid, you need to keep on playing, unless your grown-up has specifically said, “Get in the car.” And if they have, I wanna go ahead and apologize to you because you’re just gonna be sitting there for a little while until that window is completely rolled up and you are physically pulling out of the driveway. I’m not talking about sitting there about to pull out at the end of the driveway, but actually pulling out—then you’re in the clear. But until then, this is a Southern goodbye and we’re not anywhere close to leaving.

Have a great week!

~ Danny

The Amazon links in this post are affiliate links, which means that I earn a small commission from Amazon for purchases made through them (at no extra cost to you).

If you’d like to support Linguistic Discovery, purchasing through these links is a great way to do so! I greatly appreciate your support!